By Federico Arcuri

Once I started studying International Studies here in The Hague, I was not surprised by the considerable number of fellow Italian students. It is a well-known fact that more and more Italian students study abroad to escape a reality characterized by youth unemployment and lack of opportunities. Thus, I was not startled by the fact that Italy is the 3rd most represented country in my bachelor (after The Netherlands and Germany), and I was well-prepared for its natural implications – such as being added to an “Italians in Leiden + Pizza pasta emoji” group chat. However, I was surprised to learn that a significant number of Italians, like me, had already studied Chinese Mandarin in their high school, or that many Italians would select Chinese Mandarin as part of their language requirement for their bachelor’s degree. When I told people that I studied Chinese in my high school in Milan, people would often react by saying things like “Another Italian who studies Chinese, wow”, “Why are you Italians all studying Chinese?”. Therefore, I decided to do a bit of research to understand the reasons behind the perceived connection between Italian students and Chinese Studies. After a brief outline of the history of Sino-Italian contacts, I will look at the relations between the two countries, to understand whether these inter-governmental dynamics shape Italian students’ interest in the “Middle Kingdom”.

In a call to the Italian government, the Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi encouraged the intensification of Sino-Italian collaboration, and also mentioned the creation of a metaphorical “New Silk Road”. It does not only reference the famous “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) but, most importantly, it also alludes to a tradition of contact between China and Italy, which started with the trade along the Silk Road.

The Romans were pioneers in intercontinental trade. They started an indirect exchange of goods with the Chinese empire in the II century A.D. This led to the first diplomatic contacts between the two civilizations, as the Book of the Later Han records the arrival of Roman diplomats in 166 AD from the emperor “Andun” – Antoninus Pius. These increased economic contacts also explain the discovery of Roman coins and artifacts in China.

Later in history, the Silk Road also facilitated more cultural interactions thanks to the travels of Christian missionaries and intellectuals. One of the most famous examples is the Venetian merchant Marco Polo, who, having reached Kubla Khan’s empire through the Silk Road, was appointed as the empire’s foreign emissary. He lived there for seventeen years and contributed to Europe’s almost nonexistent knowledge about China with his book “Il Milione”. Polo’s visit was followed by the arrival of Giovanni da Montecorvino, the first archbishop of Beijing, in 1294, and by the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci, who was the first European to enter the Forbidden City. He ended up living in China for almost 30 years. These historical figures have shaped a perceived tradition that places Italy as a pioneer in the West’s contacts with the “Far East”.

According to a recent study from TEPSA (Trans European Policy Studies Association), this long history of contacts and trade constitutes an important asset that China is using to create a historically legitimate narrative, essential in developing a positive image in Italy. Thanks to this perceived tradition of Sino-Italian collaboration, China has created fertile ground in Italy to establish its soft power and seek economic agreements.

To understand China’s interest in Italy, it is important to look at the Italian peninsula as an essential periphery of the Belt and Road initiative. The Belt and Road initiative is a project designed to increase land and maritime routes. This entails that “Chinese loans and investments, and mostly Chinese state-owned companies, are building roads, railways, ports, pipelines, 5G networks and more around the world.” In this context, Italy’s well-established ports (Genova, Venice, and Trieste) play an essential role as Europe’s end-points to this “New Silk Road”. For this reason, China is investing in these ports, which resulted in them “almost managing 15% to 20% of European traffic”.

As a consequence, Italy became the first G7 country to be part of the Belt and Road initiative. Besides seeking trade agreements, China is also known for utilizing International aid to push its agenda abroad. For example, both Italian and Chinese domestic public opinion polls demonstrated a positive reaction to China’s significant Covid-19 Aid to Italy. It has been argued that China relied on the diaspora community in Italy, the Belt and Road Initiative Agreement, and the above-mentioned history of ancient Sino-Italian relations, to push a narrative of the two countries being a “Community with a Shared Future.” This can be exemplified by the “open letter to Italian friends” written by China’s ambassador. The BRI also had a great impact on Italian news outlets. For instance, ANSA, Italy’s most important press agency, signed a partnership agreement with Xinhua, China’s state-run press agency, agreeing to publish translated versions of Xinhua’s articles.

How does China’s quest for soft power in Italy shape Italian students’ interest in China? The same study by TEPSA shows how, besides the shared “ancient civilizations” narrative, China focuses on academic collaboration and cultural influence to assert its soft power and facilitate economic agreements. For instance, it is interesting to note that 535 Italian universities host different branches from the 12 Confucius Institutes (CI). They are also opening an increasingly high number of “Confucius classrooms” within Italian high schools – which might explain why a significant number of Italian students choose Chinese Mandarin as their language of preference within International Studies. Italian Sinologists are facing a dilemma: how to deal with the valuable help offered by the CI, without passively accepting their pro-CCP teaching of Chinese History, Politics, and Culture? An interesting manifestation of such a debate is the provoking open letter sent to Xi Jinping by Turin University and Confucius Institute’s sinologist Stefania Stafutti. They asked him to meet Hong Kong students, and to turn Hong Kong into a “place of dialogue between the West and the East”.

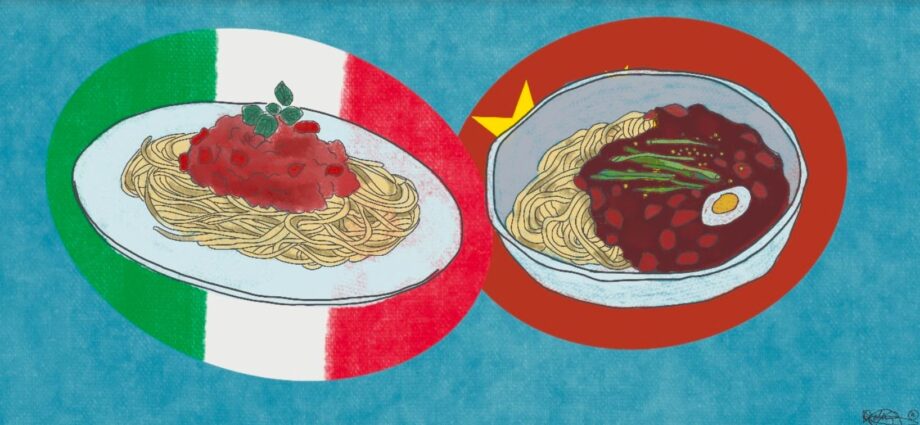

In conclusion, it can be said that China and Italy have gotten closer and closer during this pandemic and will likely continue to be so in the Post-Covid World. According to different studies, China’s quest for soft power in Italy is following a dual track, made out of promoting economic and cultural attractiveness, the latter being instrumental to the former. Covid-19 Aid and benefits from the Belt and Road Initiative trade agreements are assets which the Italian economy has to rely on for political reasons at the moment. The same could be said about other EU countries, as China is becoming the European Union’s main trade partner. But as the Sino-Italian economic cooperation is increasing, its political implications are becoming increasingly more difficult to ignore. This is evident in the debate around the presence of Confucius Institutes in Italian academia, as well as within the general public. Whereas this article has not been able to establish any correlation between the number of Confucius Institutes in Italy and a perceived tendency of Italian students to choose Chinese Mandarin as their language of studies, it is undeniable that China’s soft power is becoming an increasingly convincing explanation for a growing Sino-Italian cultural closeness.

Edited by Ricarda Bluemcke, artwork by Kelly Ville