By Arianna Pearlstein

Trigger warning: This article contains discussion of cultural and physical violence towards Indigenous peoples, particularly children, which some may find distressing. There is assistance available for those dealing with the ramifications of the residential schools. Emotional and Crisis referral services are available by contacting the 24-hour Indian Residential School Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419.

160. 182. 215. 751. Week after week, the number of unmarked graves of Indigenous children found at the sites of former Canadian residential schools kept mounting. In the time of their operation, it is estimated that roughly 150,000 First Nation, Métis, and Inuit children were sent to these so-called “schools”. There, children were forcibly and often violently torn from their cultures and forced to learn the ways of white, western colonizers. The discovery of these more than 1,000 unmarked graves has forced Indigenous communities across North America to reconcile with another form of pain imposed by settlers, and the Canadian government to find a response to these horrific headlines. While the discovery of these unmarked graves in Canada has put much focus on the government and Indigenous peoples there, the resurfacing of Indigenous boarding schools in the media has also brought increased attention to the United States’ similarly dark- yet often overlooked- history of forced cultural assimilation of Indigenous peoples through boarding schools. This article discusses the establishment and operation of Indigenous boarding schools in Canada and the United States, and examines the actions being taken in light of the discovery of so many unmarked graves. Furthermore, at the end of this article one can find additional resources to learn about Indigenous peoples today and organizations that provide aid to Indigenous communities.

The creation of Indigenous Boarding Schools

Before going any further, it is important to answer a basic question: What were the American and Canadian Indigenous boarding school systems? Fundamentally, the objective of both systems can be best summarised by the philosophy of Army General Richard Henry Pratt, who had previously been responsible for educating Indigenous prisoners of war: “Kill the Indian, save the man”. At the time of its articulation, this was viewed as a more feasible solution to certain aspects of the “Indian problem”, namely the refusal of certain Indigenous peoples to leave their lands desired by settlers and general opposition of Indigenous peoples towards integration into western life. The philosophy stated that rather than resorting to killing Indigenous peoples, it would be more effective to “feed the Indians into [western] civilization”. The way to do this, according to Pratt’s philosophy, was through a system of education in which Indigenous peoples were immersed in the ways of colonizers, or, in his words, “the civilized”. By being removed from their own native context and placed into a “civilized” one, Indigenous peoples would grow to possess a “civilized language, life, and purpose”. Consequently, they would become fully integrated into western life, losing their traditional ways of life and posing less resistance to impositions by the federal government.

Pratt’s ideas on how to address the “Indian problem” through education differed substantially from existing efforts to educate Indigenous people on western life. Previously, efforts to educate or assimilate Indigenous peoples had largely taken the form of on-reservation work, frequently led by religious officials and organizations from various Christian denominations. This was largely a result of the Indian Civilization Act Fund and the 1869 Peace Policy, which sought to improve the quality of reservation administration and education by placing it in the hands of religious officials. Though these schools were still a blatant violation of Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination, these schools were more mild than those proposed by Pratt in the sense that they were located on the reservations and local language and culture was often incorporated in one way or another. However, this schooling had been deemed to yield suboptimal results as Indigenous resistance to forced relocation continued.

Thus, Pratt’s concept of removing Indigenous people from their home contexts and placing them in ones dominated by western influences appeared a promising potential alternative method to assimilate Indigenous peoples. Previous approaches were based primarily in missionary work which had been occurring since the 1600s, in which missionaries would in some ways “live within” local systems and try to convert and “civilize” people from within. However, the system proposed by Pratt offered the advantage that Indigenous peoples would be thoroughly isolated from their own ways of life, making them more malleable to assimilating pressures. Eventually, in 1879, the federal government provided Pratt with funding to open his own off-reserve Indigenous boarding school, The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where Indigenous children were completely separated from all aspects of their culture and forced to learn western curriculum and practices. The Carlisle school ultimately became a model for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and in 1902 the office authorized the establishment of twenty-five more off reservation boarding schools. The Bureau also opened three hundred and fifty more on-reservation schools, but generally aimed to fashion them to closely resemble the off-reservation schools in which Indigenous children were completely separated from their parents.

In the United States, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children attended these schools. Oftentimes they were lured to the schools by individuals sent to collect children with promises of adventure. Other times, they would be taken from their families either as a result of intimidation, family quotas for how many children each family must send, or withholding of rations until children were provided. Despite the aggressive efforts by government and religious officials to steal away Indigenous children, Indigenous parents and communities fought relentlessly to keep their children; ultimately however, many still ended up in the schools. These schools continued to operate until as late as 1978, leaving many generations of Indigenous peoples to cope with the trauma imposed by these schools.

In Canada, these Indigenous boarding schools were referred to as Indian residential schools, and were largely inspired by the situation in the United States. As in the States, missionary schools had been in operation since the 1600s, but had not yielded the complete assimilation and removal of Indigenous ways of life that the settler government desired. In the time when the off-reservation boarding school was gaining support among the settler government in the States, then Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald sent the journalist Nicholas Flood Davin to observe the system and practices there, in the hopes that they could be of use in the Canadian effort to end the presence of Indigenous peoples. Upon his return from the Indigenous boarding schools in the States, Davin praised the American approach of “aggressive assimilation” attained by completely isolating Indigenous children from their culture and also placing them in the residential system from a young age.

Subsequently, in the 1880s the Canadian government began funding and opening residential schools for Indigenous children, while also executing other assimilationist policies. In 1894, the Indian Act was passed, making it compulsory for First Nation children to attend these residential schools. The residential schools in Canada continued to operate until 1997, when the final school in Cowessess 73 reserve in Marieval, Saskatchewan was closed. As with American boarding schools, the residential schools were often deliberately located far from reserves, in an attempt to limit the children’s contact with their cultures. Family visits were severely limited if not completely denied. In sum, these schools worked relentlessly to “kill the Indian and save the man”.

Life in the boarding schools

In the boarding schools, both in the States and Canada, Indigenous children experienced a plethora of forms of abuse, all in the name of assimilation. Upon arriving at the boarding schools, children were stripped of whatever clothing they had which did not match western definitions of typical clothing, such as leather skirts or moccasins. Additionally, the children’s hair was cut extremely short by boarding school officials. This was particularly distressing for many, because in the cultures of many Indigenous groups, short hair was viewed as taboo or even shameful, due to its association with captured prisoners. In contrast, long hair was considered among other things, a point of pride and symbol and physical extension of one’s thoughts. As if this was not enough, children were also robbed of their native names, sacred in many Indigenous cultures, and forced to take on more European ones. As a final initial attempt at separating Indigenous children from their cultures, they were forbidden to speak their native languages, bound to face severe punishment if they did.

The daily life in the schools followed a strict, military-like routine. The Carlisle School, a model for other Indigenous boarding and residential schools, clearly demonstrates this. The day was split between academic and industrial training. In the academic portion, children followed typical school subjects, such as English. However, often students were unable to actually learn much due to generally poor teaching, the material not being put in a way students, who often did not have English as their first language, could understand, or because physical and verbal abuse detracted from the teaching. Children also learned a white-washed version of history. For instance, students were taught to celebrate the Pilgrims, George Washington, and the soldiers who fought for the expansion of the United States and subjugation of Indigenous peoples.

During industrial training, girls would take on tasks such as cooking, although Indigenous foods were prohibited, cleaning, sewing, and doing laundry, while boys would farm, or learn crafts such as blacksmith work. These schools were expected to be as financially self-sufficient as possible, and so the children would often have to take on these tasks for the entire school. It was also not uncommon for children to be sent out to do such work for local white families in an exploitative form of “field trips”.

Not only that, but because Christianity was viewed as essential to the cause of “civilizing” Indigenous children, religion played a strong part in day-to-day life, and all children were expected to convert. They were made to attend Sunday school and pray, and forced to comply with strict, conservative Christian understandings of gender relations in which much time was dedicated to keeping sexes apart.

As previously noted, in addition to this intrusive and oppressive system of education, children were frequently subjected to multiple forms of abuse. Racial slurs, being called dirty and receiving merciless beatings for speaking in one’s mother tongue were par for the course. Punishments for anything which upset the school officials, even if not officially prohibited, included confinement, denial of privileges, threat of corporal punishment, or denial of food. There were also allegations of sexual assault and abuse by school officials towards the children. Not only this, but survivors of the schools also recall either directly witnessing the murder of their classmates, or saw them disappear and never return. Some students in the schools also took their own lives, and many others died from disease.

Discovery of the graves

In both Canada and the United States, Indigenous peoples had long been recounting the horrors of the boarding schools, including the death and disappearance of Indigenous children. And when in recent weeks the school grounds were examined, these claims appeared to be supported.

On 28 May, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation reported discovering the unmarked graves of 251 Indigenous children at the site of the Kamloops Indian residential school, formerly operated by the Catholic Church in British Columbia. Later, on 24 June, 751 unmarked graves were reported by the Cowessess First Nation at the site of the Marieval Indian residential school in Saskatchewan, previously operated by the Catholic Church. On 30 June the Lower Kootenay Band reported the discovery of 182 unmarked, shallow graves at another former Catholic residential school, namely St. Eugene’s Mission School. The Penelakut Tribe also reported the discovery of more than 160 unmarked graves at the site of the former state-operated Kuper Island Industrial School. These discoveries were largely made possible by the use of new technologies that can scan underground to identify objects without digging in. Unfortunately, in each of these cases, it is likely that the actual number of unmarked graves is higher. It is also likely that other unmarked graves lie hiding at the sites of the other hundreds of former residential schools in Canada.

While it is the discovery of the aforementioned graves in Canada that has prompted the most recent wave of attention, the hands of the United States are not particularly clean either when it comes to unmarked graves at former Indigenous boarding schools. For instance, roughly 222 unmarked graves have been discovered at the Chemawa Indian School cemetery in Salem, Oregon, a school which is still in operation today. In light of the discovery of the unmarked graves in Canada, several tribes in the United States have called for the grounds of the Indigenous schools to be searched for hidden remains.

Government and Indigenous responses

In light of the uncovering of more than 1,000 unmarked graves, the Canadian government issued a response. Following the discovery of roughly 751 graves by the Cowessess First Nation,Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stated that this tragedy was “Canada’s responsibility to bear” and expressed Canada’s commitment to a partnership with First Nation, Métis, and Inuit peoples to right these “historic wrongs and advance reconciliation”. Additionally, following the earlier uncovering of 215 graves by the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation, Trudeau called these findings “a shameful reminder of the systemic racism, discrimination, and injustice that Indigenous peoples have faced – and continue to face – in this country”. Since then, Trudeau has also expressed support for an independent investigation into the residential schools and suggested that the Pope should apologize to Indigenous peoples on Canadian soil for the actions taken in Catholic-operated schools. Concerning concrete action, on 30 May the Canadian government agreed to pay a lump sum amount to the survivors of the residential school system.

Despite the calls from Indigenous peoples, Trudeau, and others requesting the Catholic Church to apologize for their central role in the residential school systems and the damage it inflicted, the Pope has declined to apologize on Canadian soil, and several other high-ranking officials in the church have challenged the necessity of the church to apologize. However, under intense pressure from abroad and within the church, Pope Francis eventually agreed to meet with several delegations of residential school survivors in the Vatican. Though this is certainly a step in the right direction, it is still taking a long time for the Catholic Church to take responsibility for its role in these tragedies, and it is unclear whether this meeting will yield the discussion Indigenous peoples seek.

In all of this, First Nation, Métis, and Inuit peoples have been left demanding more concrete action. Already for decades, Indigenous peoples have been fighting policies meant to subjugate and suppress them. On several accounts, Indigenous peoples have fought to receive compensation from the Canadian government for the harm these schools imposed on them, as with the Indigenous residential schools Settlement Agreement. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission was also established to begin addressing the oppressive historical and contemporary relations between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian government, specifically concerning the residential schools. At the end of its operation in 2015, the Commission issued a final report on its findings, including 94 action points to further reconcile Indigenous-Canadian relations.

Now, Indigenous groups are calling for all action points to be concretely implemented, as only a few have been fully implemented. Additionally, there have been calls from Indigenous communities for the Catholic Church to release records of Indigenous schools where graves have been discovered; however, this has yet to come to fruition. Marion Buller, former chief commissioner of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, has also called for the Canadian government to stop contesting Jordan’s principle in court. This is because the principle, which states that Indigenous children should not be denied access to crucial services because the Indigenous and Canadian governments disagree on who should pay, is integral to protecting Indigenous wellbeing.

Indigenous communities in the United States have also demanded action to address the damage Indigenous boarding schools have done to their communities, and to be provided the resources to search other boarding schools for remains. There have been similar demands for access to records, but also for the ability to return the children discovered in unmarked graves in the States to their ancestral homelands. To begin to provide action for Indigenous communities, Deborah Haaland, the first Indigenous Secretary of the Interior whose own grandparents were forced into the Carlisle School, has established the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. This initiative aims to conduct a comprehensive review of the impact of the boarding schools.

Conclusion and resources

The discovery of more than 1,000 unmarked graves at the site of former Canadian residential schools has brought Canada’s dark historical relations with Indigenous peoples into the limelight once again. Yet for Indigenous peoples across North America, the impact of these findings is very current, adding to their communities another layer of pain at the discovery of so many children yet also relief that their stories of boarding school violence and abuse are finally being seen. Though Trudeau has contextualized the wrongs of the residential schools as a thing of the past, the trauma of the residential and boarding school systems continue to have ramifications in Indigenous communities. There is no way to bring back the hundreds of Indigenous children lost in the failed effort of settler governments to eliminate Indigenous peoples. However, it is possible to listen to, respect, and contribute as much as possible to the needs of Indigenous communities as these 1,000 plus graves are handled and more are likely discovered. Below are resources you can spread and/or use to contribute to the needs of Indigenous communities, and there are more available online.

Learn more about the residential schools (Canada): https://irshdc.ubc.ca/learn/educational-resources/suggested-resources/

Learn more about the boarding schools (United States): https://boardingschoolhealing.org/education/resources/

Organizations to donate to and resources to learn more about the residential schools: https://thediscourse.ca/okanagan/non-Indigenous-people-heres-what-you-can-do-right-now

Six organizations in Canada that assist residential school survivors: https://www.macleans.ca/news/where-to-donate-to-support-survivors-of-residential-schools/

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (United States): https://boardingschoolhealing.org/about-us/donate/

The Native American Rights Fund: https://www.narf.org/cases/boarding-school-healing/

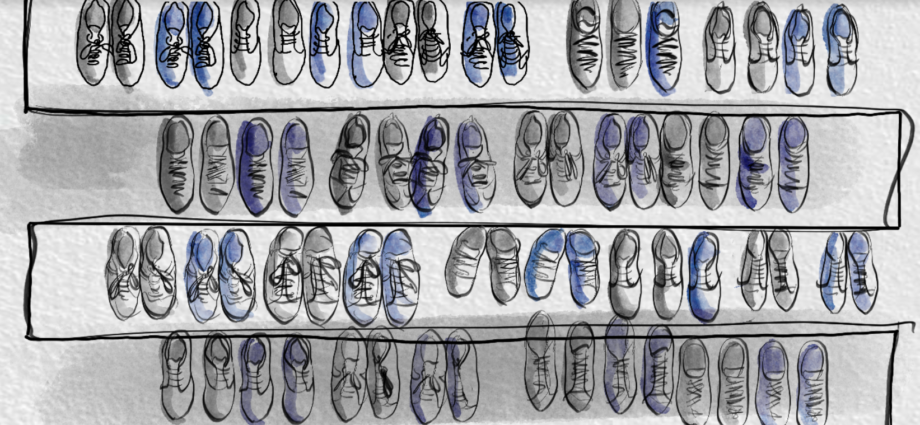

Edited by Mara Ciu, artwork by Emma van den Nouweland