Written by: Ramona Schnall

In the first part of my essay about Bookchin’s dream of municipalism, I sketched his idea of the municipality as the place to resist capitalism and environmental destruction.

But then how realistic is the picture of self-sufficiency and autonomy really? When thinking about human nature, would we really withdraw from our little intrigues and skirmishes? When picturing neighbourhood assemblies held on the smelly nylon floor in a sports centre, the picture of mundane debates about garden fences and overgrown trees emerges. And who would voluntarily sit hours on uncomfortable chairs to listen to small-town moms fight against dwarfs in other people’s gardens?

Also, does the small unit of a city mean we can’t go abroad to study? What does this mean with intercultural exchange, what impact does it have on travelling to our migrated friends in Berlin or London?

The small-town mom’s war on the tree blocking their view on her neighbour’s living room, I’m uncertain if Bookchin thought as far as that. But considering travelling and studying abroad he definitely did not argue for isolationism and protectionism. Rather, he suggested a confederation of autonomous cities that cooperate in trade and problems that exceed the capacities of the singular city. Not through a representative that decides for the entire city, but rather a delegate that would carry all the votes of his municipality to the confederation. The sum of the votes of all the cities would subsequently constitute a decision on a particular matter.

But what if egoism would steer the policies of some and cause a waste depot to pollute the drinking water source of the neighbouring city? What if one community would simply lean back and lazily observe the struggle of other municipalities to tackle climate change and reap its benefits? What if one city intentionally harms another one? After all, this waste depot would not hurt its own citizens but benefit them. What if our egoistic self-profit-oriented human nature would take over?

However, to some extent, this picture of our human nature is also produced by the current system in place: Capitalism and nation-states. But if we would trust with a leap of faith in the emergence of the libertarian municipality, in a municipal economy, we would give ourselves the chance to birth an entirely different social structure, one not based on profit but on equality, resonance and communalism. If capitalism had the force to shape human nature after its needs, maybe municipalism would harbour the same power.

Libertarian municipalism inherently presupposes and performs a different social structure to capitalism. With all its assemblies and engaged discussions over the planning of a natural resort and the production of smartphones and corn, it would necessarily change our way of relating to each other.

This active form of participating in politics is crucial to his redefinition of citizenship, without this new understanding of how we engage with decisions, our future municipalism could not persist. Bookchin imagines citizenship as rooted in engagement, involvement, and proactive participation. We can’t just sit back and close our eyes while some politicians are passing foggy laws about environmental protection. In libertarian municipalism, the responsibility for our destiny and our environment would rest in our hands.

Naturally, the constant debates and conflicts in the decision-making process would be exhaustive and time-consuming, but to this new citizenship would also count our ability to hold conflicts, to solve them. Instead of being purely draining, small-town moms fighting for the right to spy on their neighbours become solvable and productive. Conflict and compromise, we have to accept, are part of the package when living with other human beings. Also, in the world Bookchin imagines, we could give more space to holding and solving conflicts: our economy and our integration of technology in the means of production would bestow us with that.

Despite being time-consuming, the debates and conflict would necessitate intense human contact, cooperation, and compromise. Only if you manage to hold the discomfort and engage in active conflict resolution processes the seeking of neighbourhood assemblies and thus municipalism would be possible.

The overseen side effects of those open lived and celebrated conflicts within a community could be the abolition of our feeling of powerlessness. Conflicts and occurring problems would not simply remain untouched, and if answered only with the opaqueness of politicians. We as a community would be integrated in the troubleshooting. We, the neighbourhood itself, would be the carrier of responsibility and power to solve our sorrows.

Moreover, lived conflict resolution practised by municipalism holds also the potential to intensify our social networks and friendships in our close environment.

Municipalism could give us the training ground for realising that conflicts between us not only signal our differences but also hold the potential to overcome those through compromises. In effect, conflict resolution and its emphasis on active debates would actively fight polarisation.

And so, instead of alienated neighbourhood blocks, we would maybe find ourselves with dinner plans with the old granny living in the apartment below us. Maybe we would greet each other on the streets, we would buy groceries for the entire house we live in as the food would rotate anyway from kitchen to kitchen through sharing meals.

This different relation to money, economy and productivity libertarian municipalism is evoking could return our social abilities to those practised in pre-capitalist societies. We could learn a new altruism and self-lessness that still is integral in some regions of our world. This re-educated human nature could also shape thoughts of polluting the neighbour’s municipality’s drinking water source as abstract as it seems today to not do so.

And if we would be honest with ourselves: isn’t our dream of a “farmhouse” an echo of Bookchin’s? After all, isn’t the neighbourhood full of people in which we can find home and belonging, exactly what we seek to find when dreaming of the farmhouse? Is not a neighbourhood in which we feel the resonance of a community the same as the resonance we try to build in the nowhere of an old farmhouse? The only thing missing in our city neighbourhood would be the gardens and the trees. But since it is our right to determine the outlay of the grey plant-less streets in front of our building block, we might even attempt to change that.

So how to establish this different way of relating to politics, to our neighbourhood, and how to establish a different human nature? To expect that this immense project is one that we can radically implement overnight is probably a dream even more radical than the dream of the farmhouse. I guess, already embarking on the road to change is something we should strive for, as the results are the ones of another generation to reap. But we will be part of the process that will constitute change, and in this common fight, we will find the same resonance with people as in our farmhouse. Bookchin advises us to start practising the skills of libertarian municipalism already today in small gatherings where we discuss books about change, where we gather people with similar dreams of belonging and debate possible ways to reach it. Bookchin emphasises study groups, he emphasises the education of others. A long breath in the fight for autonomous cities is a given. However, if we move away from our individualistic idea of a farmhouse for a few and start to imagine the farmhouse for many, we might have the fearlessness to take a deep inhale.

One doubt, though, remains: even if we reach our goal, one last obstacle remains in place: real politics. Today we live in a world where Israel is expanding on the cost of Palestine, Russia attacks Ukraine and China is peeking at Taiwan’s sovereignty. We might manage to corrode the European states from the inside, but who says that not one of the other powerhouses takes the absence of states as an invitation to swallow one municipality after another? How can a singular municipality resist the expansionism of a state? There are so many cases in our contemporary world where not even other states managed to withhold the gluttony of a bigger one.

Within those doubts, though, also live the remains of capitalism’s idea: everyone fights for themselves. We might not be the only ones embarking on this fight. Maybe in sight of a state threatening to devour another community, the others are helping in its defence, in the defence of a common idea. It sounds like a cheap imitation of NATO, though the difference lies in the construction of the confederation of municipalities Bookchin pressures on. No representatives are voting for war, protection, or military spending but the citizens themselves with the votes their delegate brings into the confederation. But most importantly, the humans acting in defence of their idea would fight on grounds of a different conception of what their utmost inner is, what their human nature is. We would defend each other in the name of belonging.

We might not be alone in our dream of resonance. We might not be alone in our wish to resist the struggles of today: climate change, capitalism, and the feeling of powerlessness. We only need to realise the commonness of our longing to find the strength to reach out to each other.

Me writing this article, you reading this article and maybe even sharing Bookchin’s idea with friends is already proof we are on the lookout for a better future to mobilise for. And maybe from here on, we let Bookchin’s idea take hold in our hearts. Maybe we decide to integrate ourselves more into our neighbourhood. The next time the decision between moving away for a job and friends arises, we might decide against a career but for our community. And when the first conflict arises in our home base we stay with the trouble and dive into the conflict solution instead of seeking a new home. Maybe when resting in one place long enough we start to collect more and more of those people that share our common desire for a home, for belonging, for change.

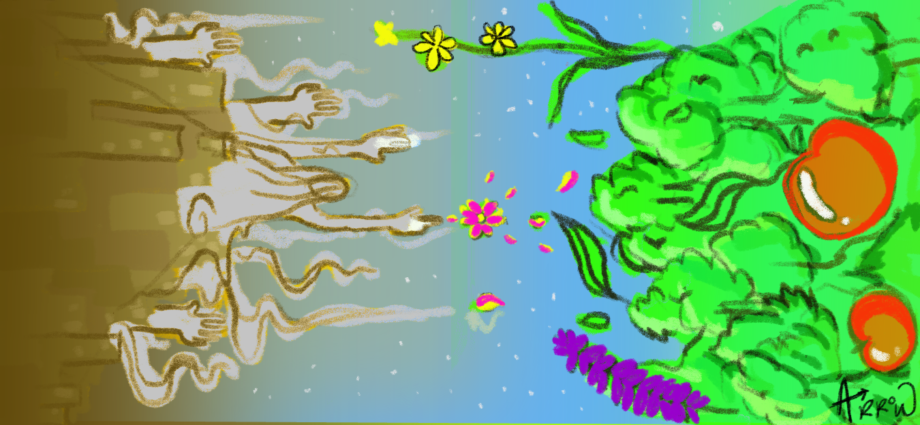

Edited by: Age Steenbreker, Illustrated by: Arrow Strayed