Written by: Ramona Schnall

There is one dream that echoes in many of my generation: The dream of a farmhouse somewhere in the countryside, a huge common area, maybe some art studies and if not, at least a little garden for butternut squash and eggplants. In our future, the idea of sharing space to raise children together, to grow old and to spend the evenings in front of a fireplace, talking about books that we read or politics we think are outrageous, seems to have bewitched us all. How often did this idea of resonance and belonging in a shared space with friends sneak its way into some small talk at a party? A number too big to count. My generation is dreaming of connection; of belonging to heal from capitalism, in community. And the farmhouse shared by friends seems to symbolise, for many, this dream’s realisation.

At the same time, in all those conversations about belonging echoes the sound of doubt. How are we to realise a farmhouse in a world where globalisation often leads to the spread of our studies and workplaces over the entire globe? The demand for mobility posed to my generation comes with a heavy burden: it forces friendships to move elastically with our journeys over the globe, a distance that often also ultimately leads to their fracture. How often have I said goodbye to a best friend without knowing if we would ever share a common country, not to mention a city? And how often have we promised to stay in touch, to call weekly, only to wake up to the realisation that those calls have long fizzled out? Even though we are accompanied by social media and new technology, and oceans between you and your loved ones can still make you feel estranged. Your life stories have simply drifted apart. Naturally, in new lifespans, you will find new friends, but at some point, finding friends and losing them again becomes an exhausting business. And so, to find a place to rest and to root becomes a delicious fantasy. But the question remains: in a world that demands restlessness, how do we root in the homes of friends we have found, how do we believe and trust in those relations? It seems impossible to build such a farm with friends in the near future.

Today, the streets and cities we are wandering in our society are structured around the principle beliefs of capitalism: isolated egoistic individuals are striving for self-profit and self-sufficiency to maximise their own happiness. Dependency on love and dependency on tenderness are dismal absurdities we learn to suppress. It is a picture of human nature we are fed supermarket milk powder from early childhood on, a picture that becomes THE natural, the only thing we human beings are capable of. Subliminally integrated into this picture of humanity also rests on capitalism’s legitimacy: greedy humans necessitate a greedy economy. If humanity is greedy, how is capitalism to be blamed for a system obsessed with the egoistic amassing of wealth? After all that is all that humanity is capable of. And so western society has become world famous for its social individualism and strict units of interhuman relations.

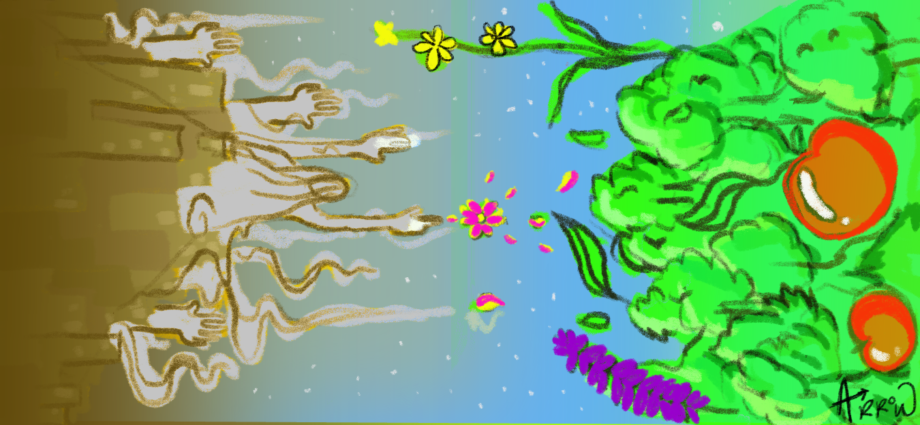

And still, we dream of a farmhouse with friends basked in love and cooperation. It might be a little revelation that human nature is more complicated than capitalism wants us to believe. The craving for resonance is vibrating in my generation and the only thing that seems to chain us to this reality is the absence of an alternative, isn’t it? Or is it again the belief in the absence of alternatives, a thought capitalism imprinted in us?

There is one writer out there who seems to suggest a middle ground, one that balances the idyllic version of a farmhouse and the longing for connection and resonance in a community. Somewhere in the 1980s, Murray Bookchin proposed a concept founded on the idea that our neighbourhood can be the fertile ground for resistance. A resistance to capitalism, to the malfunctions of contemporary democratic politics, to the environmental crisis and our inherited isolationism. He elaborated this idea in the book “The Next Revolution”. In those pages, he focuses on the city as a social and economic structure of our society. A concept inspired by the city-states of the Greek polis, but updated into a modern-day version that not only includes men in politics but everyone regardless of gender or ethnicity. In its centre of the libertarian municipality stands the refocus of power.

Today, power rests in the hands of a small elite priding themselves with a degree. Already in 2018, it was clear that in the United States politicians are constituted by the upper class and in Germany, research found that 80% of party politicians are academics. They pass laws for a society whose needs they don’t understand simply because they never lived in their life realities. Still, the state is the level where those laws are born and realised.

And exactly here, on the state level, Bookchin claims, lies the root cause and prime solution to racism, economic deprivation and inequality, in short capitalism. Often the state is failing to fulfil its social contract on the level of the villages, which is not big news. We only have to look at the educational differences between communities and the lonely fight of cities against the effects of climate change to realise the state can’t answer the needs of its cities. However, the state, so Bookchin, is not only failing the local needs of its citizens but also is responsible for the divide between people based on class, race, ethnicity or religion. The state is inherently an entity that is always based on an idea of us within the border and those who are not. And if we give in to national ideologies, quickly also the idea of us being much more superior than the Others manifests.

Additionally, power in a state is always concentrated in the hands of few, even in representative democracies. Today those with power are often the ones who made it in party politics. Those, however, already enjoyed a more privileged upbringing and education than most of the working class. And so, those who have a say in matters of cheaper public transport or about new abortion-right laws are often in far distance from the real outcomes of those policies. Politics today is constructed from those able to participate in party politics and others who are bystanders, but it is never something that we as normal citizens can actively engage in. But when politics and decisions are reduced to elections held once every four years, then, so Bookchin, democracy remains a farce, and our image of politics a disfiguration of the world. Instead, our inability to change the course of events, especially for our younger generation, gives birth to feelings of powerlessness. To remove, thus, the power from the state and concentrate it in municipalities and citizens’ assemblies, to concentrate power in the hands which the decisions are affecting, would remove the imbalance between decisions and effect.

In his essays, Bookchin claims that this would have the most beneficial effects on the environment and society. This makes sense so far when you consider capitalism and the state as the root causes of structural racism and the exploitation of the environment and humans. In the centre of libertarian municipalism would not only rest the principle of participatory politics but also of a participatory economy. Here the power over production, land and products would rest not in one CEO but in the hands of all members of a city.

In contrast to the popular idea of a Cooperative, that also distributes the shares of a company equally to its workers, the libertarian municipal economy is not integrated in a capitalist environment. This capitalist environment, Bookchin points out, often results in the infiltration by capitalism in the Cooperative itself. To survive in a growth-addicted environment, you must bend to the necessity to expand, or else you are swallowed by its greed. In contrast, the municipal economy would exist outside of capitalism, without the necessity to grow, and a vertical power hierarchy benefiting from surplus value. The municipal economic environment would presuppose that all the relations between production, land and consumption are not separated by profit-seeking but are holistically owned by us. Competition causing growth addiction would be redundant, and so would exploitation and division of people and labour.

But then how realistic is the picture of self-sufficiency and autonomy really?

For that, read the 2nd part of this essay.

Edited by: Age Steenbreker, Illustrated by: Arrow Strayed