By Joanna Sowińska

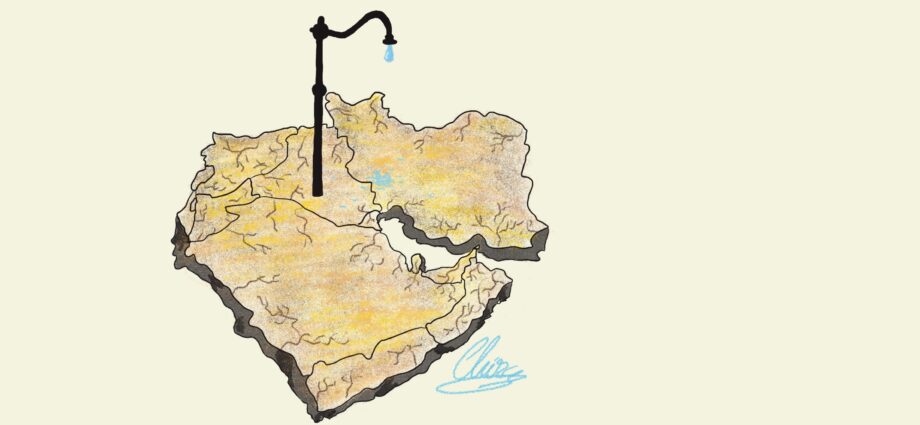

Living in a country such as the Netherlands sometimes makes people forget about their basic privileges. While the ability to shower once or twice a day may appear marginal to people in most developed countries, two-thirds of the global population (4 billion people) and close to half of the world’s largest cities experience water scarcity. Water accessibility can be outlined in two dimensions. Firstly, its physical availability, and secondly, its distribution throughout the countries. As a matter of fact, only 0.014% of Earth’s water is fresh and accessible! 97% of water is saline and the remaining 3% is hard to extract. From a more political perspective, water’s distribution is extremely uneven, which fuels a considerable number of conflicts in water-scarce areas. Ensuring satisfactory access to water is becoming increasingly important for countries, especially considering population growth trends, climate change, and the expansion of the agriculture sector. This is especially true for developing countries. A case study illustrating the terrible effects of water scarcity are water conflicts in the Middle East.

The Tigris and Euphrates rivers originate in South-Western Turkey and both cut through Syria and Iraq. Not that long ago, those rivers became a point of contention for numerous speculations and disagreements regarding their water use. In fact, during the times of the Ottoman Empire, Iraq was the main water consumer from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, having built underground irrigation channels in order to expand its agriculture. It can be said that at the time, Iraq fully enjoyed its access to the rivers, as neither Turkey nor Syria used significant amounts of water from them. Nevertheless, this situation quickly started to change in the 70s when the Middle East, and especially Turkey, experienced rapid growth of its population. Of course, this had a direct impact on the demand for water, a precious and key natural resource for the development of the arid area. Because of the urgency of the situation, Turkey decided to take action in 1975 with the Southeast Anatolia Project. The goal of this project was to construct 22 dams and 19 hydropower plants across the Tigris-Euphrates basin which required a massive expansion of Turkey’s irrigation canals.

Currently, the project is more than halfway completed (60%) and continues to consume water from the rivers. It has been calculated that once the SouthEast Anatolia Project comes to an end, the water flows from the Tigris and Euphrates will be reduced by 40% into Syria, and more drastically, 80% to Iraq. This presents an enormous change in water consumption in Iraq; one that differs drastically from its historical dependency. Additional tensions can be observed between Syria and Iraq, as Syria has also recently started the construction of dams in order to maximize its water flows from the rivers. Of course, this triggered a huge wave of anger from the Iraqi side who threatened to blow up the Syrian dams. Noticing growing tensions, Turkey did not stay neutral to this statement and threatened both Iraq and Syria of entirely cutting off their access to water. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers case demonstrates the impact a natural distribution can have on international diplomatic ties. Furthermore, this shows that the likelihood of tensions resulting in war is increased when a country’s natural resources are at stake.

Studying in a country where, on average, one person’s household consumes 52m2 of water per year, it is really hard to imagine how our life would look like without the daily use of the bathroom, toilet, kitchen, a washing machine, or even a pool during those warm summer days. However, this life we live is very different from the reality of billions of people. Coming back to the example of Iraq, the issue of water shortage is way more complicated than it appears. In addition to the unfortunate distribution of the rivers flows, Iraq also suffers from a poor government response in providing clean and drinkable water to its population. This is because water availability and quality are easily altered because of war. Due to its long history of religious, environmental and land conflicts, Iraq has often been exposed to war, which has deteriorated its water infrastructures. As a result, Iraq has encountered significant challenges in terms of the spread of infectious diseases such as malaria through its water supplies. Despite some actions undertaken by International Organizations and the Iraqi government itself, the prevalence of corruption in the country poses an additional challenge to the availability of clean water in the country. The lack of incentive of local elites to invest in water cleaning systems for the population outside the selectorate, accompanied by bribes in water monitoring mechanisms, the issue appears to be unresolvable.

Although geographical luck remains the main factor accounting for the quantity and quality of water, the political and institutional framework of water-scarce areas must not be neglected. Accordingly, because of the autocratic nature of most Middle Eastern states, including Iraq, one can observe that states value competition over cooperation. In addition, autocratic political systems are often characterised by a ‘thirst for power’ of a small corrupt elite which prevents the population from politicising the issue of freshwater scarcity.

Edited by Yasmina Al Ammari

Artwork by Chira Tudoran