By Arianna Pearlstein

Trigger warning: This article discusses eating disorders, specifically anorexia nervosa, which some may find distressing. However, if you feel you are struggling with an eating disorder, please scroll to the end of this article for several resources.

Imagine, there is a loud buzzing noise in your head. It goes from morning to night without a single pause. Even when you are trying to do basic things- working, following a lecture, making breakfast, going out with friends- the buzzing drones on. At times, the noise becomes so overwhelming that you are physically debilitated by it to the point that you can do nothing. Of course, there are things you can do to temporarily dull the noise, but every time you do, it only comes back louder, and louder, and louder, until it is deafening and completely debilitating.

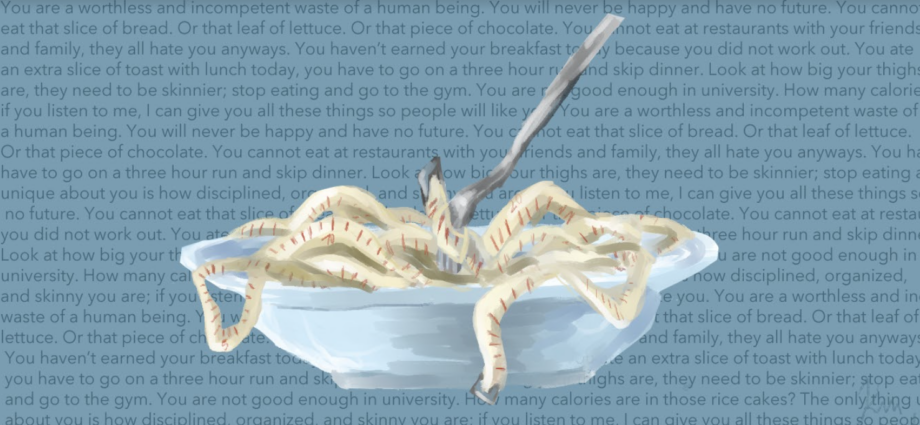

Now, replace the nondescript buzzing with thoughts typically associated with anorexia nervosa. Where thoughts like- You are a worthless and incompetent waste of a human being. You will never be happy and have no future. You cannot eat that slice of bread. Or that leaf of lettuce. Or that piece of chocolate. You cannot eat at restaurants with your friends and family, they all hate you anyways. You haven’t earned your breakfast today because you did not work out. You ate an extra slice of toast with lunch today, you have to go on a three-hour run and skip dinner. Look at how big your thighs are, they need to be skinnier; stop eating and go to the gym. You are not good enough in university. How many calories are in those rice cakes? The only thing unique about you is how disciplined, organized, and skinny you are; if you listen to me, I can give you all these things so people will like you. You are a waste of space that will never amount to anything- are commonplace. These thoughts and others play in your mind non-stop on the maximum volume, even as you try to do basic tasks. As the thoughts scream in your head, you start to believe them. And because you believe them, you start to give in to them. Thinking about food 24/7, googling the number of calories in a rice cake, looking up how many sit-ups you have to do to burn those calories, body-checking for hours, cancelling dinner plans, the list goes on. Eventually, you start to find comfort in these absurd behaviours so that you cannot live without them.

This is what it means to have anorexia nervosa (AN). It is an ugly disease, but one that all too often is glamorized as the “model healthy lifestyle” or dismissed as something women do to get attention. These and other stereotypes can be life-threatening. In this article, I address these, explain what anorexia nervosa is, and what to do if you feel you are struggling or know someone who is.

Let us first answer a basic question: What exactly is AN? At its core, AN is a mental illness characterized by deliberately restricting food and (caloric) drink consumption, over-exercising, and an intense fear of gaining weight. However, there are many additional ways that AN can present itself, including strict rules about what one can/cannot consume, rules about when they can consume “approved” foods and how much, disordered body image in which an individual thinks they are much bigger than they are, and low weight or weight loss.

Formally, AN is divided into two types, the binge/purging type and the restrictive type. The former refers to a form of anorexia in which individuals purge or abuse laxatives to remove food from their system, particularly after they have eaten a “forbidden” food or large quantities of food. This helps them feel as though they are compensating for what they have eaten. Contrastingly, restrictive anorexia is one often mistaken for praise-worthy self-discipline, in which individuals avoid various foods, particularly carbs and high sugar/fat foods, and consume far fewer calories needed to maintain a healthy weight. In other words, restrictive anorexia is a form of self-starvation. Regardless of form, those struggling with AN also often struggle with depression and anxiety, making it an extremely complex mental and physical disorder.

A sub-dimension of the broader question, what is AN, is: what causes AN? Ultimately, there is no single cause, but rather AN is believed to be caused by a combination of environment, personality, and biology. One of the most well known environmental dimensions affiliated with AN is social standards concerning appearance and thinness as portrayed in media. Specifically, the constant direct and indirect idealization of thin, model-like figures to which children are exposed from a young age in movies, stories, and the like can be detrimental. The triggering impact of thin culture can also arise more locally within the family or community. This can occur when one comes to feel they are praised or valued based on their body or there is pressure to attain a particular body type; being bullied or experiencing abuse, even if not directly related to one’s appearance, also contributes to AN. Furthermore, children being exposed to comments about “good” and “bad” foods or diet culture also contributes to AN. Partaking in activities such as ballet, elite-level sport, or pageants has also been known to trigger AN. Those with perfectionist personality types or those who struggle to confront conflicts are also at a higher risk of developing AN. Concerning biology, hormonal irregularities, for instance, those associated with hyper- and hypothyroidism and polycystic ovary syndrome, are the underlying cause of AN which is exacerbated by the aforementioned environmental factors. There is also believed to be a genetic component that makes individuals predisposed to AN, but the precise nature of the genetic component is not completely clear.

However, despite the psychological, physical, social, and interpersonal havoc AN brings, there are an unbearable amount of myths and stereotypes that seek to diminish the circumstances of those with AN or bar certain groups from having their AN recognized and treated. I address some of the most common ones below:

- AN is not an actual medical condition, it is just something people do for attention: This is just plain wrong, there is no other way to put it. While it is the case that AN does tend to draw attention in public or in relationships as individuals start to become more withdrawn, to say that AN develops simply out of a desire to gain attention is harmful and inaccurate. Additionally, it is also often the case that individuals work quite hard to hide their As briefly touched on earlier, AN develops for a host of reasons, but attention is not one of them. This can include coping with past trauma or current life stresses, or to regain a sense of control over one’s life or punish oneself as a result of poor self-image. These actual drivers of AN are complex and deeply rooted in one’s life experiences, not a surface-level desire for attention. In reality, more often than not the attention one receives while struggling with AN is fuel for further spirals, as comments such as “oh you are so thin,” or “wow you are so disciplined with your diet, I wish I could be like that”, reinforce the view that one needs to engage AN behaviors to be accepted. Thus, in contrast to the common myth, attention resulting from AN further fuels the condition, but is not a reason for which it develops.

- You have to be underweight to have AN: Given the nature of AN as a condition involving constricting food consumption, the common assumption is that all those with AN are (dangerously) thin; however, this stereotype has long resulted in the dismissal of those who do not fit the stereotype. This stereotype is held not only by those outside the medical community, but also within the medical community, and is extremely problematic. The standard Body Mass Index typically considered to indicate AN ranges from 15.00 to 17.50 depending on the individual’s size and weight. Yet this range misses the fact that AN is a psychological condition, meaning that although weight can certainly be a symptom, so long as one is presenting the thoughts and behaviors associated with AN, her/his/their condition is just as valid as one who fits the stereotypical picture. In reality, only roughly 6% of those with eating disorders are considered underweight. Recently, the medical community has started to reckon with this and has added an “ atypical anorexia” diagnosis for those who exhibit AN behaviors but are above the typical weight range. However, this move has been critiqued as representing internalized fat-phobia both in the medical community and society, because the term marks one as “other” based on body type rather than their psychological state. There is still much to be done to combat this stereotype because AN does not discriminate, and anyone’s AN is valid so long as they present the psychological and behavioral dimensions, regardless of weight.

- Only white women struggle with AN: There are two components to this stereotype- race and gender, which affect perceptions on whether one can have AN and the prospect of treatment. On the former, the prospects of attaining a diagnosis and treatment for AN vary substantially by race, yet there is no particular reason that people of color would be less susceptible to AN. Regardless, studies have found that people of color are less likely to be diagnosed with, or receive treatment for, AN, and this is exacerbated by socioeconomic gaps. The second dimension is gender, particularly that AN is a woman’s condition. First, this overlooks the fact that men, particularly if they are gay or queer, also experience AN. For instance, the UK eating disorder organization BEAT found that 25% of those with AN are male, but that these men often felt that their struggles were dismissed or attributed to something other than AN amongst both family and medical experts. Another group often overlooked is those who identify as transgender . For instance, a 2015 study in the United States has found that those who identify as transgender are roughly 4 times more likely to struggle with AN compared to their cis gender counterparts. The reasons for this are complex and vary per individual. For some, AN is a coping mechanism for the trauma of the bullying or abuse they face for expressing their identity. For others, however, AN serves a practical purpose, namely to alter one’s appearance to align more with the gender they identify with. Trans men are particularly vulnerable to developing AN, as AN behaviors can help them to develop a more masculine figure as they lose secondary sexual characteristics including the fat on their breasts, hips, and butt, in addition to losing their menstrual cycles. And even though trans individuals are more likely to develop AN, they often struggle to attain a diagnosis or treatment due to the stigma surrounding trans identities. In sum, AN does not discriminate by race or gender identity; yet the medical community and society at large are highly discriminatory when it comes to validating and recognizing the experiences of those with AN. This disparity is dangerous, and until it is bridged individuals will be left to struggle with a life-threatening condition simply because they do not match the description.

- “All” you have to do to recover from an is “just eat”: When I first built up the courage to tell my family and close friends that I was struggling with AN, the most common response was “oh okay so you just need to eat more” or “okay hahaha let’s go eat ice cream and fast food and all that until you gain back the weight”. Quite frankly, this was probably the most damaging reaction I could have received because it propagated the idea that my illness was not so much an illness but rather a slight feeling of discomfort about eating. This idea completely overlooks that AN is a psychological condition often connected to poor body image and self-hatred that expresses itself through food and eating. Not only that, but this notion also overlooks how serious AN is in terms of mortality. AN is currently one of the deadliest mental health conditions there is, second only to opioid addiction specifically, AN has a mortality rate of roughly 10%, and with tens of millions of people worldwide struggling with AN this is no small number. Recovering from AN is in reality primarily focused on working to improve one’s self-image, challenge negative and self-defeating thoughts, and learning healthier ways to cope with life stresses. Of course, improving one’s relationship with food is part of recovery, because AN expresses itself through food. However, this relationship is healed through a slow and gradual process that is oriented more towards self-image rather than through just eating junk food until you are healed.

What to do if you think you are struggling:

I would now like to turn to those who have been reading this article who know that they or someone they know may be struggling with AN. While I am no doctor, I have lived with AN for 10 plus years of my life, and so would like to provide some very basic advice to anyone who may need it.

- Be patient: As empty as it sounds, being patient with yourself and others is one of the most fundamental steps in beginning to recover from AN. If you yourself are struggling, above all else be patient with yourself as you take small steps towards processing the presence of AN in your life and building up the strength to reach out to others and pursue treatment. Additionally, once you have built up the strength to tell others, be patient with them as well. For those who have never experienced AN, learning that someone close to them is struggling with it is also difficult, particularly in terms of understanding how to help or what the condition is in the first place. Relatedly, if you do not struggle with AN and someone close to you tells you they do, you will also have to have an incredible amount of patience, with yourself and them. The process of letting others in on, and recovering from AN is like a never-ending minefield you have to navigate blindfolded, and so the individual going through it will inevitably do some frustrating things including withdrawing, not letting you in, getting upset, etc. The most important thing is to keep making sure they know you support them and keep checking in and asking what you can do to help. If they say nothing, it is not intended to harm you, just keep being there.

- Seek professional treatment: This one is daunting but necessary. There are a lot of reasons you or the person struggling close to you could provide to avoid treatment, whether that be clinical, psychological, nutritional or all three. Or, even if you or the person close to you knows treatment is necessary, it may be difficult to take it seriously and commit to the amount of vulnerability necessary for treatment. Personally, I was in the latter camp: I knew I needed help, but I thought therapy was pointless and just about tricking you into having “good vibes”. However, to those in that situation, here is a small bit of wisdom that helped me stick with it and save my life: You can always quit. If recovery is really that bad, or that pointless, or that tortuous, you can quit. Go back to living life the way you were before. But you cannot quit until you have recovered everything you have. And maybe, when you have given it your all, you will find that recovery is worth it. With that said, when initiating the process of seeking treatment, the primary question is always: How do I start? Well hopefully this can help clarify a little: In the Netherlands, to receive treatment one must first go to their general practitioner, who then refers one to a psychologist. Subsequently, that psychologist will determine what form of treatment is necessary, and then if applicable refer one to the place in which the designated form of treatment is available.

- Be an advocate for yourself: While this applies to life in general, being able to advocate for yourself, both against yourself and when pursuing treatment, is particularly important. Due to the stigma surrounding AN and the stereotypes surrounding what someone with AN “should” look like, even attaining a diagnosis can be a process. It may be that doctors act sceptical of you or do not believe what you say or do not consider it an indicator of AN or any other eating disorder. For instance, for myself I was sent to several other medical practitioners including a gynecologist and endocrinologist before they would finally give me the AN diagnosis I needed to pursue recovery. In sum, you have to continue to assert that you need to be looked at for an eating disorder even as they try to push you elsewhere. Once you manage to begin the formal process of recovery, you also have to be adamant about your needs. This can be difficult because most of the time you do not even know what your needs are. However, if you ever feel like you do not match well with your therapist, the treatment is having harmful effects, etc, you need to voice these concerns immediately, because you are always the top priority. Finally, and perhaps most difficult, you have to advocate against that part of yourself that tells you to give up or give in. This does not have to be anything massive, it can be as small as getting up to take a shower when you feel like all you can do is lay in bed or laying in bed when AN is screaming in your head that you need to go exercise off any calories you just consumed. No matter how big or small, these steps towards advocating for yourself in recovery are just as essential as recovery itself.

Anorexia nervosa is not a glamorous thing. It is an ugly disease that slowly but surely progresses until it is all-consuming. AN is also not about wanting to be praised for being skinny. It is a serious mental health condition that can ultimately take one’s life if left untreated. While much of the pain caused by AN is similar for those who experience it, there is no one look or life experience that unites everyone with AN. That is the tricky thing about conditions of the mind. We are often, especially in medicine, so quick to examine the exterior that the complexities of the mind are sometimes overlooked or pushed to the side. Going through the process of recognizing your AN, opening up about it, and pursuing treatment is honestly one of the most mentally demanding tasks one can undertake. That being said, so is the experience of accompanying someone you love through that process. While recovery undeniably comes with some low points, the best advice I could give is this: Quit if you want, but only after you have given recovery everything you have. Because maybe, just maybe, it will be worth it.

Resources:

Self-help resources:

https://www.yourhealthinmind.org/mental-illnesses-disorders/eating-disorders/self-care

Helping someone with AN:

https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/supporting-someone/supporting-somebody

https://www.verywellmind.com/how-to-help-someone-with-an-eating-disorder-5088664

Clinics: (You will likely first need a reference from your GP)

https://www.edreferral.com/netherlands/treatment-center

https://www.rivierduinen.nl/eetstoornissen

Finding a nutritionist can also be helpful for some; for this it is best to contact your GP

Edited by Gunvir S. Paintal, artwork by Mira Kurtovic