By Margaux Marzuoli

Having discussed the emergence of the climate crisis and established the current need to move away from fossil fuel combustion as a source of energy, the second part of this article addresses potential solutions. These include, yet must not be limited to, renewable energies (including photovoltaic solar panels, wind turbines, and hydroelectric dams) and nuclear energy.

It must be acknowledged that the applicability of these solutions vary per country, and that public perceptions impact governments’ choices to privilege certain solutions over others. Overall, a solution for country A might not be feasible in country B, and future decisions should take into consideration the specificities of each country.

Renewable vs. Nuclear Energy

There are many articles and youtube videos comparing the desirability of renewable energy and nuclear energy, however these often fail to assess the yields of different energy technologies. In this context, yield can be defined as the difference between the energy required to create the technology and the energy output of this technology. All energy technologies require the extraction of non-renewable materials from the Earth, whether it be coal, uranium, or lithium. Furthermore, many of the materials used in energy technologies, like some of the concrete used in nuclear power plants (made radioactive), turbine blades, and solar panels, are not recyclable. As such, it is in our interest to prioritize energy technologies that require few raw materials and yield the greatest quantity of energy.

Considering this, nuclear energy appears to be the most favorable energy source as nuclear fission requires very small quantities of uranium or plutonium and produces very large quantities of energy. Although the building and maintenance of nuclear plants requires energy, the yield of this technology is significantly greater than any other renewable technologies.

Indeed, renewable energies fall short on their ability to deliver large quantities of energy. This is in big part due to the fact that they depend on the weather. Energy Sage explains that in one year “a 2,430 MW Vogtle nuclear plant could be expected to generate 21 million MWh per year, enough to power about 1.75 million residential households”, meanwhile “a 3,500 MW of hypothetical solar power would produce just under 6 million MWh of electricity (…), enough to power 500,000 homes”. The company points out though, that nuclear plants are more expensive and take more time to build, and thus argues in favor of solar panels.

It is interesting to note that since nuclear energy requires very small quantities of raw materials, it produces very low quantities of waste compared to other technologies. This is important when considering increasing urbanization and the space available for solar farms. Indeed, nuclear power plants and the storage of nuclear waste do not require much space. Although many are concerned by the storage of nuclear waste, there are examples of successful long-term storage facilities and evidence shows that nuclear energy is among the safest energy sources.

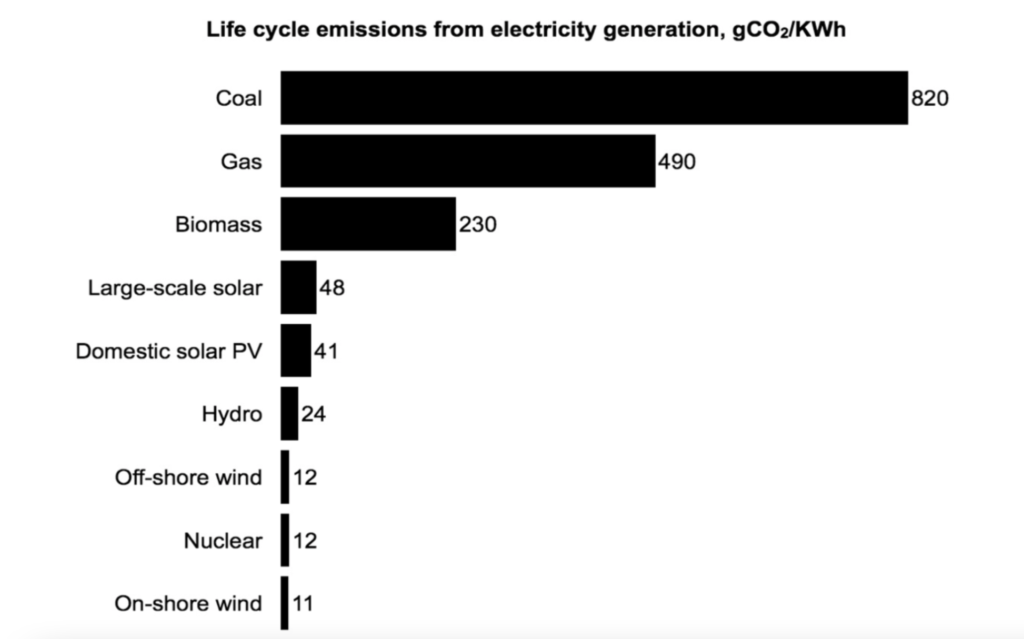

Most importantly, the debate on renewable versus nuclear energy fails to acknowledge the use of gray energy in the creation, maintenance and operation of energy technologies. In its Fifth Assessment Report, the IPCC mapped out the carbon emissions released along the lifetime of different energy technologies, yet it remains unclear to what extent non-renewable carbon-intensive energy sources, and their emissions, are involved in the creation and maintenance of renewable and nuclear energies. Acknowledging this potential underestimation of the life cycle emissions of low-carbon energy technologies, the graph below shows that nuclear energy remains less carbon intensive than many renewable technologies.

A Need for Change

Although the International Energy Agency forecasts a growth in the capacity to generate electricity using renewable technologies, the broader debate on this issue fails to address the fact that we are mainly using gray energy to create renewable energy and that our energy production is limited by non-renewable materials. There is also a need to bring the issues related to the exploitation of our land and its peoples to the forefront of this discussion. These problems are of paramount importance and require a change in the structure of our economy.

Overall, we must stop ceaseless accumulation and change our language of valuation. This implies moving away from an economy focused on exchange-value and moving towards an economy centered around use-value. Ultimately, our modes of production need to become regenerative and distributive by design.

To achieve any change though, we need to act now and effectively reduce our carbon emissions.

Jean-Marc Jancovici, professor and founder of The Shift Project, points out that coal is a “domestic energy” – an energy that is used within the country where it is extracted – and thus to reduce our carbon emissions significantly it is imperative that we start by having a conversation with the United States, China, Russia, Kazakhstan, South Africa, Germany and India. Esther Duflo, winner of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics, also points to the uniqueness of this crisis, highlighting that it mostly affects the poor but can only be resolved by the rich.

Edited by Uilson Jones, artwork by Teresa Valle