By Chira Tudoran

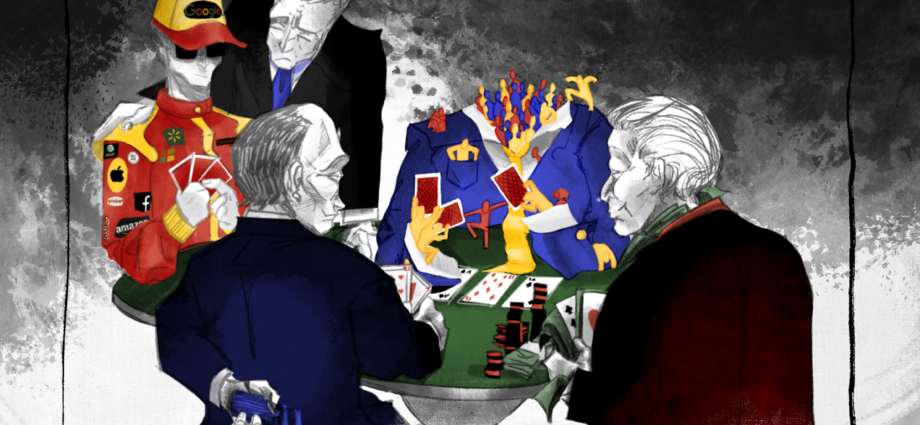

Imagine a poker table. There are 3 big guys, and 27 little guys. The big guys are playing individually, and they are playing hard. The smaller ones, however, are falling over each other arguing on which move to make next. The big guys represent the United States (US), China, and Russia. And the little guys? That is what the European Union looks like in the global sphere at the moment. Is there a way out of its current situation?

Ton van Loon is a Lieutenant General of the Dutch Army (retired). Van Loon led missions in Kosovo and Afghanistan, and he was commander of the German-Dutch Army Corps. He now teaches at military academies, is a senior fellow at a German think-tank, and a regular guest lecturer at several universities, such as Leiden University. Sphaera Magazine has gotten the opportunity to interview him. The interview addresses the departure from the model of the post-Cold War order, the new global economic and military reality of the EU, and the case for Strategic Thinking.

Since the interview covers many issues, we have decided to divide it into two parts.

Part 1

Tudoran: Since the fall of the Iron Curtain, Europe has once again seen great changes. After WW2, initially the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), followed by the European Union (EU) developed into the ultimate collective civilization model. The EU’s crown jewels were the peace it held within its borders and its economic power. At the time of the 1990s and 2000s, the US worked closely with the EU, Russia was no longer a threat, and China was still developing. Everything looked perfect. In 1989 Fukuyama wrote about this new era which he referred to as the end of history. How do you think Fukuyama’s prediction holds now in 2020?

Van Loon: When the wall came down in 1989 most of our politicians believed that it would now automatically be alright. Francis Fukuyama had just written his famous book ”The End of History and the Last Man”. His optimistic view: “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government” fitted perfectly in the desire to reduce costs and forget that results from the past are never a guarantee for the future.

History ending or not, one thing was certain, we (in Europe) would cash in the peace dividend quickly and thoroughly. Wars, conflicts, and crises, in general, were now seen as something that can only happen somewhere else. Peacekeeping meant sending troops to places less fortunate where people did not yet fully understand that the end of history had arrived. Of course, this also resulted in a lack of real political backbone. The military was hit hard and now we have to acknowledge that most (if not all) European armies can no longer fulfil their constitutional task to defend the country. It also resulted in the US basically becoming the policemen of the world. Even NATO’s article 5 defense became fully imbalanced with the US taking a disproportional part of the burden. The COVID-19 crisis might well be the first global crisis since the end of the cold war where the US leadership was absent and badly missed. The “West” has gotten used to looking somewhere else (preferably to the US), meanwhile it has been very clear for a long time but this crisis literally shouts: Europe you need to wake up.

The volatile world in which we now live is slowly resulting in a change of mind. Policy thinking is influenced by the understanding that not all neighbours are always nice. The Russian invasion into Ukraine and flight MH17 being shot down demonstrated painfully that the illusion of eternal, and most of all cost-free, peace in Europe was just that: an illusion. Peace is not free and requires hard work and (financial) commitment. If one thing is certain it is uncertainty. Former German defense minister, now chairperson of the European commission, Ursula von der Leyen said at one of the meetings preparing the 2016 defense whitepaper (= a vision paper or a study) that to her the speed of change was the most striking element of today’s defense policy. We need to start accepting that we are not very good at predicting the future.

The truth is: Fukuyama’s book has always been a lot more nuanced than commonly thought. Peace was never something that could be taken for granted. We need to realize that governing is not about managing day to day business and even less about popularity polls. In a recent interview in Dutch magazine “De Groene Amsterdammer,” Fukuyama explains that the democratization wave reached its pinnacle 10 years ago, now we live in a different world that moves in a different direction. Not recognizing that, would be a big mistake (Thomas, 2018).

Tudoran: When the Cold War ended Europe had no enemy anymore, so what was there left to do and to strive for? Money. It has become very apparent that the EU has had its focus on money and the economy. This can be seen in its military spending, or lack thereof to be more exact, where the US pays the NATO bill in exchange for economic privileges. After all, why spend money on the military when there is no war? Could you explain a bit more about the transition the EU has made in its economic and military strategies over the years?

Van Loon: One element of the post-Cold War world is the almost holy belief in the markets as THE solution. Not only the willingness of governments to react to crisis but also the resources to do so were dramatically reduced in the 1990s and early 2000s. Private, and often global, companies took over crucial tasks in for instance healthcare. Banks became too big to fail and money became something almost abstract. The world now knows several hecto billionaires. The COVID-19 crisis shows very clearly that there should be limits to what states should be able to privatize and what not. Do we really want vaccines produced only if a profit can be made? In the military domain, money has become the (only) deciding factor. Several “white papers” have all tried to define the defense needs, but forecasting has proven to be difficult. Attempts to define the threats and calculate the capabilities needed to deal with those threats have not yet been very successful. For one because threats have been changing at such a pace that planning ahead is just not possible. But often the wish is also father to the thought. Which means required capacities are needed to cope with future risks. This would result in high costs that could easily be written down to accommodate yet another budget cut. To be very blunt, in an ideal world the military is a waste of money. But, the world is not perfect, not even close. The best guarantee to avoid war is to have a credible military to deter potential predators. Because of the end of history effects militaries, especially in Europe, have been cut to fit the declining budgets. We did not really ask ourselves what we needed, but most of the time what we could (more honestly wanted) to afford.

The same can be observed in other areas where intervention is needed in crises, but basically not very useful when the crisis is not imminent. Migration for instance. At the peak of the refugee crisis in 2016 and 2017, the capacity to deal with arriving refugees (housing but also screening and administration) was increased substantially. When the flow decreased this capacity was quickly reduced again (why waste money if not needed). At the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, the capacity to quickly deal with refugees became a bottleneck. The World Food Programme recently briefed the UNSC on the developments in Africa. The numbers are truly grim with over 250 million depending on external aid and a shocking (worst case) potential 300.000 death toll per day. If the combined ecological (locust), viral, and economical disasters hit Africa this will lead to a human catastrophe, and of course also to a serious increase of migrants fleeing this misery (Charlton, 2020). Are we ready for that? Are we planning for that? Or are we going to look the other way (again) and hope someone else is going to deal with it. I don’t think we are ready.

Tudoran: I agree with your last statement, though I have to ask how are we going to deal with the issues mentioned? We have to take into consideration non-state actors, such as the big multinational companies. They also hold enough influence to lobby and manoeuvre themselves in politics. One area of concern is the health sector, but the cyber environment (e.g. 5G networks) should also not be overlooked.

To go back to a previous point, you said that some capabilities that are needed to deal with crises are a constitutional responsibility of the state that cannot be driven by money and therefore are more important than the economy. My question is then:

How would this work with 27 countries in a cohesive manner? After all, the EU has a unique political framework when compared to the US, China, and Russia.

Van Loon: To quote German Minister of foreign affairs, Heiko Maas (2020): “We live in a digital world in which two poles are becoming increasingly pronounced. Silicon Valley is one of them. That is the American model which, let’s make no bones about it, focuses exclusively on maximising profit. The second model, the second digital pole, is emerging in China, in Beijing. Digital possibilities are used there to repress. Neither of these models can serve as a model for Europe”.

Another problem is that more and more the line between state actors and non-state actors is getting blurred. That was already the case with terrorist groups and insurgents (such as the Taliban), but now some (big tech) companies have become so powerful that they are more and more becoming powerbrokers in their own right. Besides governments being too focused on the economy, it is also concerning that multinationals hold so much influence on society. Looking at your metaphor of the poker players it seems to me that especially for the US it is the question who is really playing the game. The big-tech companies are more or less playing their own game and their influence on the government is really big. In Europe this perhaps is not (yet) so problematic, but here too lobbying and the link between politicians and big business is becoming an issue. The most telling example is perhaps former German chancellor Gerhard Schroder who now works for Putin’s Gazprom. For Chinese companies there is often a direct link between companies and the state (as is the case in Russia). In the US this is not the case but too much money has been used to buy influence. Think for instance about the money flowing into election campaigns (Mercer, 2016).

Europe should re-focus its attention to its core values. The same applies to NATO as well. An alliance is much more about shared values than it is about hiding behind a stronger ally.

End of Part 1

Edited by Helena Reinders

Artwork by Emma van den Nouweland

References will be posted at the end of Part 2.