By Lea Schiller

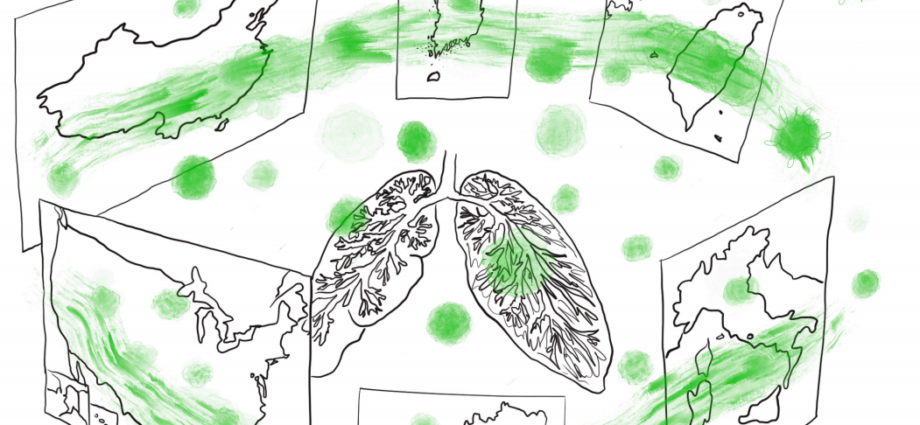

When China first reported the outbreak of a new variant of lung disease to the World Health Organization (WHO) on December 31st, the virus that has now become a household name—SARS-CoV-2, had already been on course for nearly a month. What followed were measures of unprecedented level: once it became apparent that the closing of the Huanan Seafood Market – believed to be the point of origin of the pandemic – wouldn’t be enough to contain it, multiple cities were placed under lockdown. However, the virus had already been spreading for weeks at that point, during which the government attempted to downplay the severity of the situation. Travel restrictions swiftly imposed by other countries were criticised as “overreactions”, and doctors such as Li Wenliang, who tried to warn others about the disease and later fell victim to it himself, were silenced by the police. When China did react, they did so on a scale that has never been seen before – but the large number of infections across the country indicate that they were much too late in doing so.

The WHO has praised China for its response – but a closer look into Asia’s democracies paints a different picture: they proved to be much more efficient in dealing with the virus while avoiding the restrictive measures China had put in place. Many countries that stumbled in their response to the 2002 SARS outbreak now had contingency plans in place and were thus much better prepared. The response in these countries has largely depended on early travel restrictions, strict quarantine and widespread testing from the beginning.

In Taiwan, despite frequent travelling and proximity to China leaving its population in a particularly vulnerable position, a large outbreak was prevented altogether. This was made possible by implementing measures such as screening all new arrivals as early as January, mere days after first news of the outbreak in Wuhan. The country had overhauled its entire public health system after failing to contain SARS – and next to increasing physical capacities, a new legislative now provides the basis for a quicker response to a coming epidemic. Although case numbers experienced a sharp increase in South Korea, the spread was slowed down considerably from almost a thousand new cases per day in late February to less than a hundred by mid-March. By increasing testing capacities early on and testing up to ten thousand people per day, authorities were able to track and isolate the infected quickly enough to get the spread under control.

When the disease – named COVID-19 by the WHO – arrived in Europe, it seemed to come as a surprise. Case numbers in Italy began to skyrocket in a matter of days, and many other countries quickly followed suit.

In Italy, health officials suspected that the virus had been circulating long before the first locally transmitted case was discovered, as hospitals in the north of the country had been reporting a high number of unexplained pneumonia cases. And while countermeasures were put in place as case numbers started rising exponentially, many people carried on without caution in the days leading up to the countrywide lockdown, contributing to the spread.

In neighbouring Austria, there was hesitation to close the ski resorts during a highly profitable time, even as visitors and customer-service workers started testing positive for the virus. From there, it spread to other European countries, who hesitated to restrict movement across borders, awaiting EU-wide measures – until they too experienced rapidly rising case numbers.

In the US, the fate of their efforts was decided much earlier – in 2018, President Trump fired the national pandemic response team, and did not install a replacement. And even as the novel coronavirus arrived in the US, the government hesitated to respond. Officials repeatedly blocked doctor’s attempts to start widespread testing, and by the time it finally begun, cases were discovered among people with no recent travel history – indicating that the virus was already being transmitted locally. Additionally, the decision to rely on the American Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to produce testing kits instead of using the ones already approved and distributed by the WHO would cause weeks of delay. The tests initially distributed by the CDC turned out to be flawed – a severe setback to a country that had already started testing too late. To put the US context in perspective: by March 16th, the US had only tested twenty-five thousand people. Italy had tested more than five times that number, and South Korea even more than that, even though both countries have a smaller population. At the time the US had roughly five thousand confirmed cases, but the number of unreported cases in the country is likely to be much higher.

While the situation certainly is dire, there is a lot to be learned over the course of this period. This pandemic has shown us that even in a globally intertwined world with unprecedented movement, the outbreak of an infectious disease does not leave us helpless – quite the contrary: with thorough measures, preemptive preparation and quick implementation, countries like Taiwan and South Korea have shown the world that the virus can be brought under control.

Edited by Caitlin Elston-Weidinger

Artwork by Chira Tudoran