By Joanna Sowińska

Politics is odd. It is often characterised by the lust for political power, and the Polish government is a clear example of this phenomenon. In 2015, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (eng. Law and Justice), a right-wing, populist, conservative party won the national elections for the second time since its creation in 2001. It is particularly known for its Euroscepticism and poses a threat to the quality of democracy in Poland.

A clear example of the negative influence of the ruling party over the citizens can be outlined. It should be fundamental for each country to ensure adequate sanitary standards, such as well-prepared hospitals (with sufficient amounts of face masks, medical gloves, etc.) but also to create some moral unity among their citizens in the age of Corona Crisis. By contrast, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość seems to be working against basic decency and acts under the cover of the Corona Crisis with an attempt to pass its ideology. In fact, the Polish parliament is recently trying to pass five more bills instead of devoting more serious attention to the sanitary crisis. The ruling party claims to only execute the will of the majority who voted for them in the elections, but this decision remains frustrating for many Polish citizens. This article focuses on two of the bills which impede both the right of self-determination and the basic sexual rights of Polish citizens.

The first bill aims to ban abortion. Abortion rights in Poland are already ones of the most restrictive in Europe, since it is only allowed in such cases as rape or when the woman’s health is at stake. Thus, a lot of Polish women decide to get abortions abroad. When this is not possible often due to financial reasons, some women get illegal abortions even, which obviously puts their lives in danger.

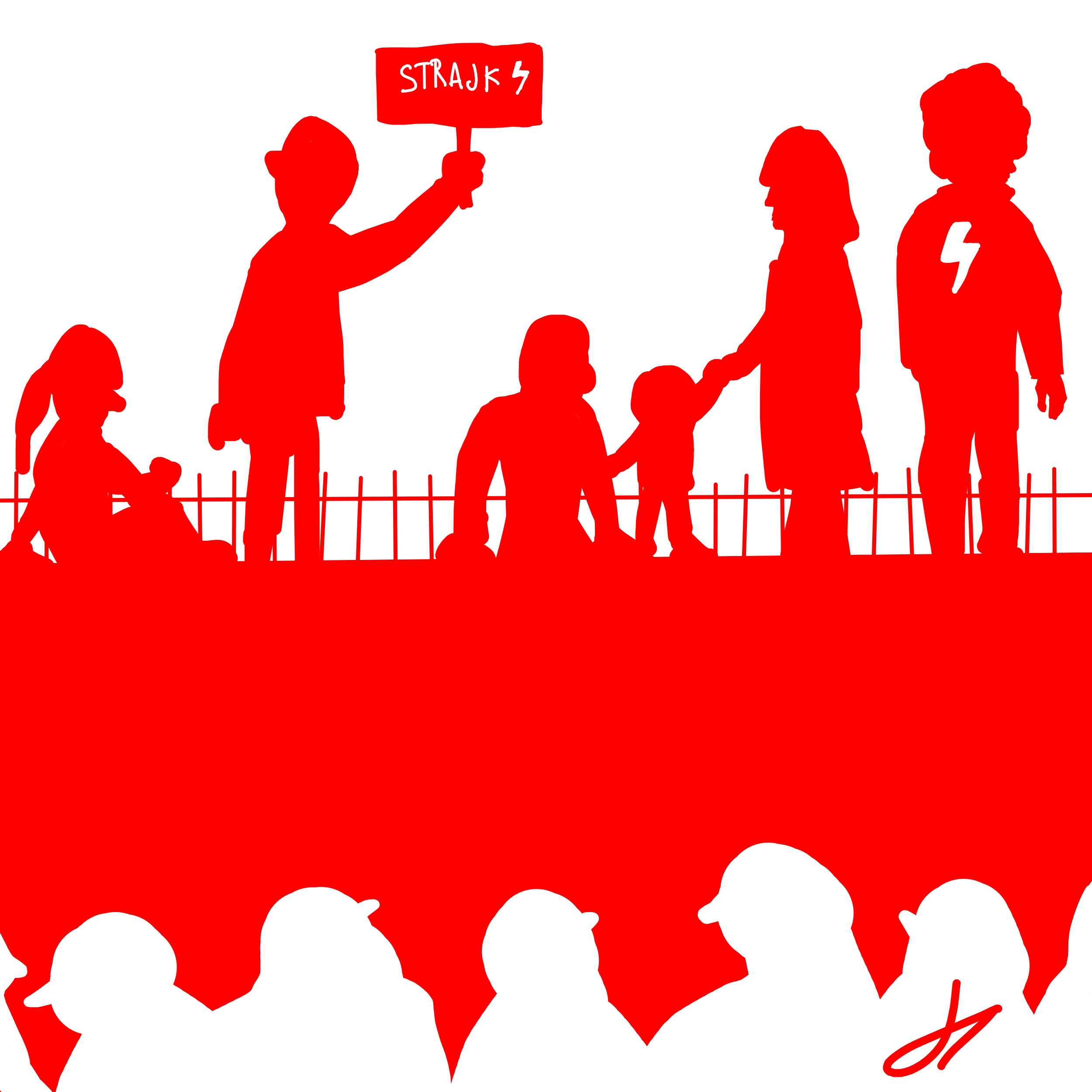

The new bill seeks to even further strengthen abortion conditions. On September 2016, a bill which aimed to restrict abortion completely was debated in the lower house (pol. Sejm) of the Polish government. However, it was tied down under civic pressure, since thousands of Poles have protested against the bill, both off- and on-line, under the name of Czarny Protest (eng. Black Protest) and a symbol of a black umbrella. As a result, in October 2016, lawmakers voted the bill down. The Black Protest is undeniably an example of a successful civic force that can make a change in regards to oppressive bills. Nevertheless, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość did not change its position on abortion. It tries, once again, with these new, less strict, however still really repressive laws compared to European standards bill.

The second bill targets sexual education in a very oppressive manner. In fact, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość would like to criminalize sexual education. Accordingly, the signatures for the design of this bill were collected by the Stop pedophilia organization, known for its homophobic opinions and oppressive attitude towards sexuality. The project states that public promotion of information on sexuality to minors is to be sanctioned by up to 2 years of imprisonment. Similarly, the promotion of this information by means of mass communication such as social media would be punishable by up to 3 years in prison. In other words, the bill states that any person involved in sexual education among young people would be at risk. This, of course, appears as shocking to Poland’s European peers who generally offer satisfactory information about sexuality to young people. One can imagine the impact this law could have on the decision making of youngsters concerning sexual consent, the use of contraception and the effective protection against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

The proposal of these two bills raised remarkable anger among a large part of Polish citizens who are opposed to them and highly disagree with the fact that Prawo i Sprawiedliwość party decided to pursue its political objectives when the country did not even reach its peak of COVID-19 cases yet. Furthermore, opportunities for protest are highly altered given the “dislocation impediment” which further complicates people’s expression of disagreement. An online movement called Nie składamy parasolek (eng. We don’t fold our umbrellas) was created by Internet users in order to show their disapproval. As a result, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość politicians’ social media got overflowed with numerous protest posts, which gives us hope for a better future.

Poland is a country in which sexual and reproductive rights are already very limited, and abortion laws are one of the most repressive in Europe. Of course, the example of the proposal of these two controversial bills is probably not enough to draw any meaningful conclusion about democratic backsliding occurring in Poland. However, plenty of other examples could be outlined in order to argue for this hypothesis. This applies for instance to the purposeful reform of the National Council of the Judiciary and the Constitutional Tribunal of Poland by the Polish lower house. In fact, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość is accused by the European Union of strategically appointing its allied judges. This, in turn, enables Prawo i Sprawiedliwość to propose and pass many controversial bills through the national parliament. This situation is further alarming, as Martin Schulz, the president of the European Parliament, claimed that the circumstance in which these judges were appointed was against the European Constitution.

The question could be thus asked once again. Is the Polish government fading away from democracy for which the Polish movement Solidarność fought for so long in the 1980s? Is Poland really on a bumpy road back to authoritarianism?

Edited by Zuzanna Mietlińska

Artwork by Oscar Laviolette