By Arianna Pearlstein

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, ignited by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery among countless others, the modus Operandi of police disproportionately criminalizing Black Americans has taken center stage. The question many Americans are asking themselves is how to go about police reform to ensure that low income and BIPOC communities are also kept safe rather than deliberately targeted? In examining the history of police in America, it becomes clear that the system isn’t broken; it was largely created to persecute Black Americans, and is doing just that. Since policing as an institution was designed to preserve the way of life and interests of white elites, long-term change will not come from internal reforms. Many argue that instead the answer lies in defunding the police altogether.

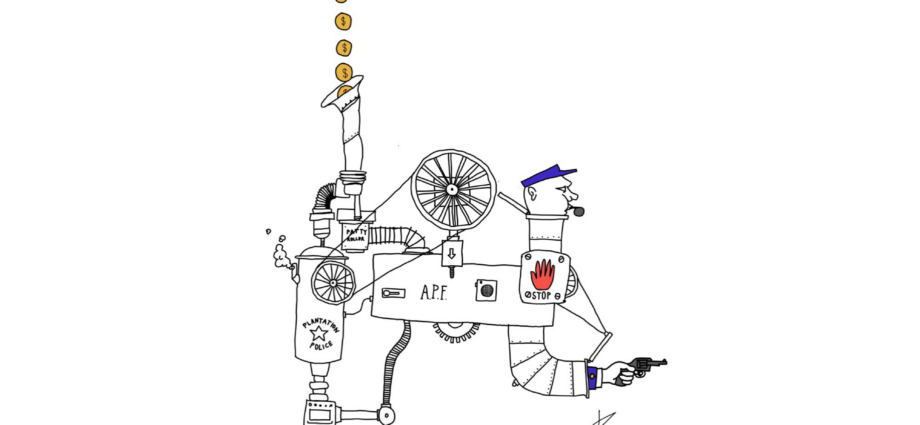

The precursors to the modern police force emerged in the early nineteenth century not to punish individuals for crimes, but to control the behavior of minorities including immigrants, Indigenous individuals, and Black individuals out of fear of uprisings by these groups (Source). In the North, predominantly white, male, volunteer night-watch patrols were created to quell disorder amongst the aforementioned “dangerous” groups. While Black individuals in the North were targeted, they were far more explicitly abused by early police in the South. As explained by Gary Potter, a professor of Criminal Justice, white elites formed volunteer slave patrols, known as patty-rollers, to capture runaway slaves and return them to their captors, monitor the behavior of Black Americans to preserve the interests of white slave owners, and use threats and violence to strike fear into Black communities to prevent rebellions which would threaten the Southern way of life contingent on slavery (Source).

Gradually, these vigilante groups became increasingly intertwined with local governments, and by the end of the nineteenth century most larger cities had established official police forces. The racial targeting which shaped the slave patrols and night watchers persisted, and together with the 13th Amendment of 1865, which abolished slavery except as punishment for a crime, gave rise to the criminalisation of Black individuals by the police as we know it today. As Khalil Muhammad, a Harvard historian, details in a Vox interview, the exercise of basic political, social, and economic rights by Black individuals in the South came to be viewed as criminal acts (Source). Black individuals were presumed to be criminals because this secured the ability of white southerners to continue to exploit the Black population after the legal abolition of slavery (Source). And who is tasked with protecting society from dangerous criminals– the police.

Muhammad asserts that modern criminalisation in the North really took off during the Great Migration during World War I, when Black Americans fled to the North in pursuit of freedom. Muhammad exposes how census data, which revealed the disproportionate incarceration rates of Blacks in the South, and police bureau statistics led to the proliferation of the notion in the North that Black individuals were using their newfound freedom to commit crimes, when in reality their very being had come to be defined as a crime in the South.

Consequently, throughout the North and South, the rights and behaviors of Black Americans came to be severely restricted, and the police were responsible for enforcing these restrictions and more generally securing the interests of white Americans against their allegedly criminal Black counterparts. These racist origins have remained integral to policing in America. To this day, the police continue to enforce a criminal justice system built on racist foundations, disproportionately arresting and using force against Black Americans (Source).

Thus, it’s clear that police in America continue to fulfill their original purpose: suppressing Black Americans among others; so the system isn’t broken. And because it isn’t broken, internal reforms such as banning chokeholds and creating a National Police Misconduct Registry (Source) won’t fix the reality that Black individuals are excessively subjected to police brutality. Such internal reforms may minimize the symptoms of police brutality and Black criminalisation, but they will not cure the disease.

To achieve real, lasting change, Americans should not spend time “fixing” a system which is, according to its original purpose, achieving precisely what it was created to do. Instead, efforts should be focused on defunding that system altogether to invest in measures that will actually keep all communities safe since that police system has deliberately stripped many fundamental rights from BIPOC communities.

What does defunding the police entail? Defunding involves reallocating funding away from police departments to frequently overlooked social service providers and other government agencies and community components including public education, healthcare, childcare, housing, and the like (Source). For one, this would enable communities to address their underlying struggles, such as poverty and homelessness, which have been used as reasons to increase police presence in their neighborhoods and are themselves the result of deliberately racist practices such as redlining. Philip V. McHarris and Thenjiwe McHarris also noted in an op-ed for the New York Times, that using a portion of police funds to establish mobile support teams for issues such as mental health, domestic violence, and substance abuse would minimize the police brutality faced by Black communities and to constructively de-escalate such situations (Source). It is important to note that defunding the police is distinct from abolishing them. The former involves maintaining police forces but reallocating funding, whereas the latter involves disbanding police forces and unions in addition to reallocating funds (Source).

Defunding could enable Americans to begin to rid themselves of the disease of systemic racism, upheld by police forces and which has plagued the police system since its founding. In establishing a new system where Black Americans and other people of color are not automatically assumed to be criminals and thus in need of constant oversight and control by police, but instead are given the resources, both in daily life and in times of crises, to live freely and safely.

Americans have an opportunity few thought would be available in our lifetimes: the opportunity to truly make systemic racism a thing of the past rather than a painful reality we hide from. Since this chance is so rare, we cannot push for reforms that will not enable long-term healing and progress. The police have been a racist institution from the start, and so healing will not come from trying to fix a working system. Rather, we must defund the police so they are no longer the only strong actors in public safety, and invest in measures to better BIPOC communities.

BIPOC: Black, Indigenous, People of Color

Black: I say Black rather than African American to acknowledge the breadth of diverse individuals who are part of the shared and multifaceted history, culture, and identity shared amongst those who identify as Black. This includes those affected by the African diaspora, those from the Carribean, and Africa. For more on this, refer to the Associated Press (Source) and the Urban Institute (Source).

Edited by Caitlin Elston-Weidinger

Artwork by Oscar Laviolette