By Sasha Zinchenco

Did you know that the Carnival in Brazil had a much more violent sister festival? This other event, called Entrudo, was finally prohibited in 1830 in order to give way to the more “civilized” Carnival. Initially it involved brutal and violent pranks and throwing of disgusting liquids such as semen or urine. Although forgotten by nearly everyone, including most Brazilians, the history of Entrudo is essential in order to understand the making of the Brazilian identity in the post-colonial period and the Carnival fever that happens every year since.

Entrudo in Europe has a completely different meaning. This pagan festival is mostly celebrated in Portugal and symbolises freedom and a fun-loving spirit. In Lisbon, the pranks involved making the staircases slippery so people would fall, and adding smelly liquids on doorknobs so that those who tried to open the doors had a stinking hand for the rest of the day. In the countryside however, the festival involves more costumes and dances, usually depicting demons and eccentric characters. The Entrudo of Lazarim is particularly famous, but its content has almost nothing to do with the adaptation taking place across the Atlantic Ocean in Portugal’s biggest colony.

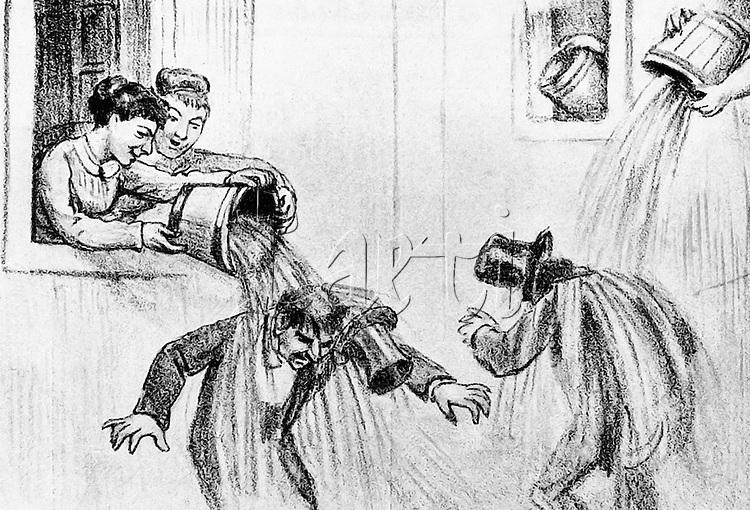

Back in the old days, Brazil also suffered under the hands of the inquisition, also known as “Visitação do Santo Ofício”. In 1590, an inquisitor reported back to the Portuguese crown about an incident that took place in Bahia during an Entrudo. During one of the celebrations, a bucket of faeces, that slaves would carry from their master’s house and throw in the sea or river, was dumped on a young lady passing by. When the inquisitor interrogated locals, someone stated that such incidents were commonplace every year. Seldom, pranks cost people their lives. A French architect named Grandjean de Montigny, who came with the royal court, died from pneumonia two weeks after a prank.

There were two types of Entrudo- each celebrated by a different class. The “upper” Entrudo was celebrated by the elite and their households, which consisted of a relaxed atmosphere and moderate pranks, like throwing food and other things that would not necessarily hurt others. Slaves could only participate at the receiving end of the pranks, whereas being the prankster was considered rude for a slave and could result in punishment. However, the “lower” Entrudo was wholly different where indulgence was enjoyed by slaves, poor people and immigrants. This was celebrated in the streets and was more pandemic than in Portugal. The main difference in the intensity of versions was, while in Portugal the pranks were less threatening, like cutting up a big dummy of an old woman and presenting hair to bald men so their wives wouldn’t leave them for younger men, the Brazilian version was an embodiment of mass hysteria and denigrating pranks.

With the intention to counteract this festival, with special enthusiasm from Emperor Pedro II, Carnival became a bigger part of Brazilian identity. Copying the masquerade balls from New Orleans and Venice, but adding more indigenous and later African elements, the aristocracy attempted to educate the masses into a more “civilized” and “European” festivity. Although succeeding in almost erasing Entrudo from the Brazilian mindset, some elements of it still persist in modern-day Carnival, demonstrating how “symbiotic” culture can behave.

Edited by Mariya Nadeem

Artwork by Chira Tudoran