By Juni Moltubak

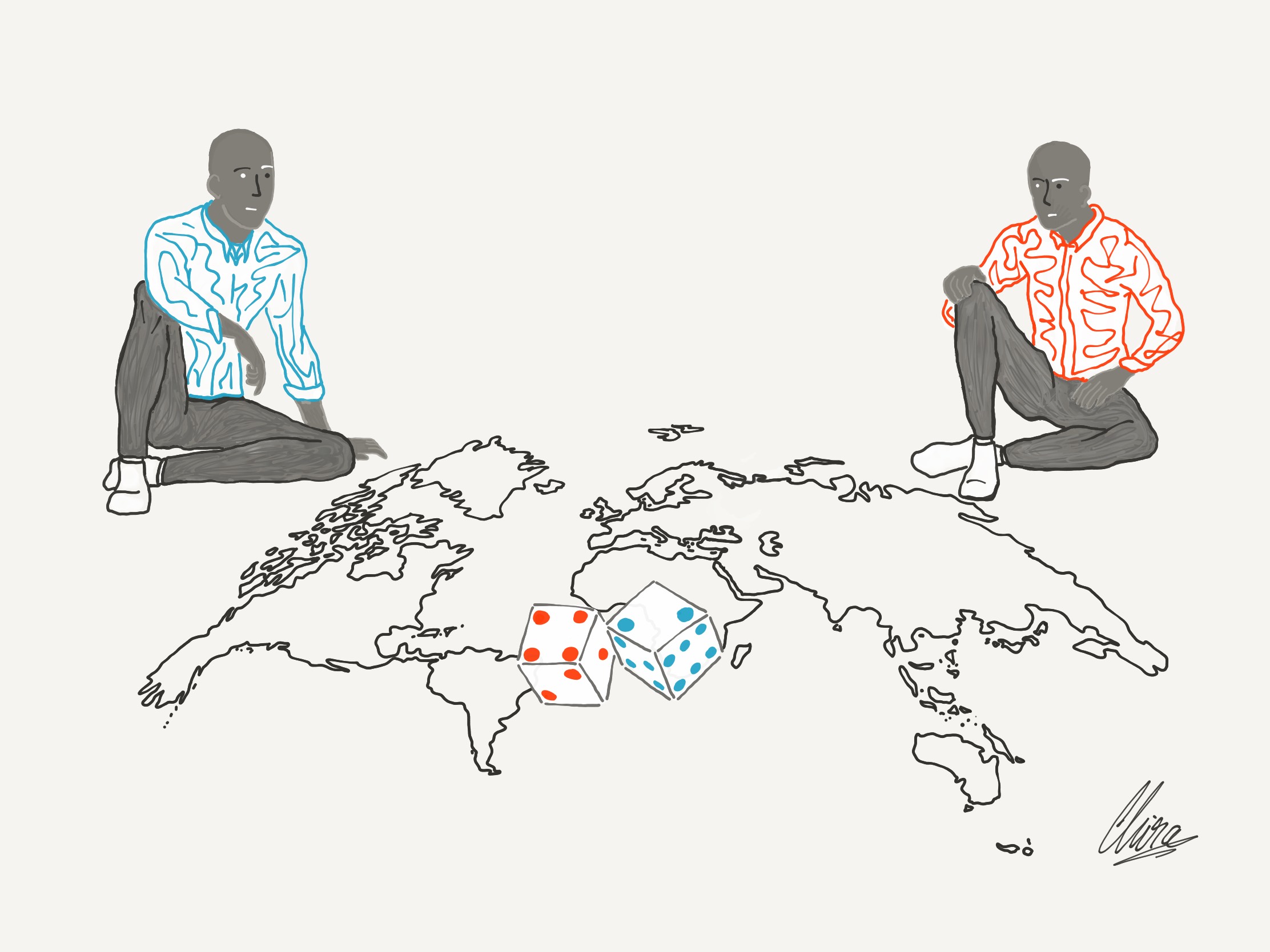

Climate change is in a state of crisis. And so, many would argue, is democracy. Some may say that we need to sacrifice certain democratic rights in order to solve the climate emergency, whilst others claim democracy is the very key with which we can solve the problem. Does one challenge the failure of the other? Can neither live if the other survives?

On November 5th 2018, BBC’s Diego Ortiz published a list covering “10 Simple Things to Act on Climate Change”. The article tells people to stop driving their car, fly less, stop eating meat, shop less and shop differently. It is direct and informative, but unfortunately ineffective. The reader is left with a feeling of guilt that leads nowhere. Some might follow the article’s advice, and actually cut down on driving, go vegetarian and start flying less, but at the same time, others will certainly oppose and protest against such moralizing interference. They will feel like threatening forces from the outside are trying to dictate their lifestyle. This has the unfortunate, but nevertheless logical effect that some people think fighting climate change cannot be done without deprivation of freedom, and thus cannot be done democratically.

This leads us to a significantly greater issue; is our current democratic and economic system designed to fight climate change? At the very least, I would say that it does not provide a very beneficial environment for doing so. Humans are simple beings, and this often has the consequence that the need for affluence and physical goods is the deciding factor when decisions are to be made. The majority of people living comfortable lives are not willing to give this up without any immediate reward or compensation, which unfortunately means that democratic decisions more often than not focus on material comfort and safety for the individual, rather than the long-term well-being of our planet.

The solution might be to decrease the amount of democratically delegated power in society. But will a political message like that ever win ground? In his best-selling book “The Road To Unfreedom” (2018) the American historian and Yale professor Timothy Snyder explains how reducing democracy not only is a sacrifice many people are willing to make, but to many in fact a highly appealing solution. Snyder claims that today’s society is dominated by so-called politics of eternity. This phenomenon was a natural effect of the so-called politics of inevitability, a somewhat similar, but yet fundamentally different concept.

Politics of inevitability was, according to Snyder, a wave of optimism that occurred after the Cold War ended. The general perception was that society had gone through all stages of history, and reached its final destination; a peaceful, liberal democratic state that would last forever. The future is good no matter what you do, so why would you care about politics, governance or preserving democracy and its institutions?

As mentioned, the politics of eternity was a natural effect of the politics of inevitability. Shortly explained, the politics of eternity is one without belief in the future at all. As soon as society realized the impossibility of the politics of inevitability, they slowly transitioned into a mind-set of negativity and hopelessness. The future will be bad no matter what you do, so why make an effort to change it? This is the mentality that to a large extent dominates the debate around climate change today. And, more importantly, it has developed into the idea that democracy has lead us into a state of futurelessness and chaos. That, according to Snyder, is why a large amount of the population view a decrease of democratic power, and thus an increase of autocratic power, as the most effective and sustainable solution to a prosperous future. But is that the solution we need in order to fight climate change?

The threats to democracy today are undoubtedly many, and Snyder manages to explain from where the positive image of an autocratic future originate. It is evident that today’s economic and, to a large extent, political system is not well suited to fight climate change, neither on an individual nor top political level. Personal and material prosperity is fixated on and designed to exploit our society as well as our planet. However, in opposition to what some (or according to Snyder – many) might believe, this does not mean that we need more autocracy, but quite the opposite – we need more democracy.

Firstly, authoritarians are no better at green governing than democratically elected officials. In reality, they are arguably worse. An autocratic position does not facilitate for peaceful cooperation, neither domestic nor international, which both are desperately needed in the fight for climate justice. The growing attraction towards authoritarian-like governance that Snyder presents makes the need for a stronger democratic effort evident.

Secondly, a thriving economy and an innovative market is more often than not connected to democratic governance. As we see that the green industry is booming like never before, environmentally friendly products are increasingly requested, and businesses and corporations are following up on the consumers’ demands, it is evident that a strengthened democratic movement can and will lead to greener solutions.

Finally, it is important to remember that one person alone cannot solve the climate crisis. Considering the fact that the crisis itself is influenced and fuelled by a wide range of factors, the solutions we find need to be complex, diverse and creative as well. Not only is it impossible for a single (autocratic) leader to find his way out of the climate problem, but varied solutions, creativity and innovativeness does undoubtedly tend to flourish in democratic environments. In addition to this, one could argue that a frequent change of leadership is the best way of bringing new ideas and fresh perspectives to the table. Different leaders have different approaches, which can be fortunate in order to find the solution that works best.

In the end, the key is to understand that a change in lifestyle does not necessarily mean decreased freedom, or less democratic rights. And as Nico Stehr writes: “We need to recognize our changing climate as an issue of political governance and not only as an environmental or economic issue.” In other words, in order to fight climate change we need to fix democracy, not discard it.

Edited by Sasha Zinchenco

Artwork by Chira Tudoran