By Zuzanna Mietlinska

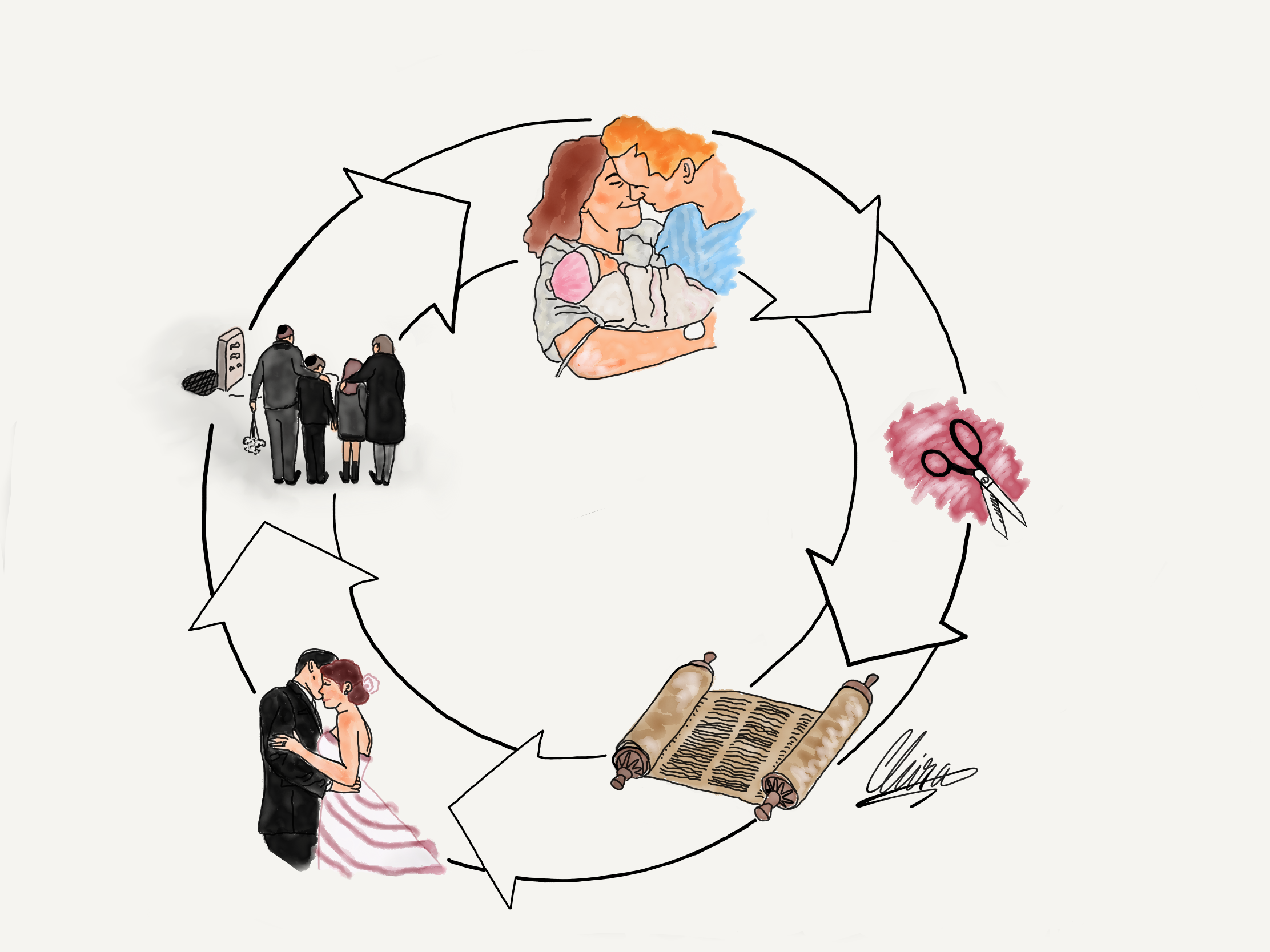

The following article presents a short introduction to the Jewish lifecycle – namely, the most important events for every practicing Jew – from birth to death, through circumcision, bar mitzvah and marriage. All these occasions are associated with a set of customs and practices, common to Jews across the present-day diaspora.

Birth

For practicing Jews, unlike for Christians, human life begins at birth. This tenet has consequences in relation to the possibility of abortion, which is not only permitted, but also advisable when the mother’s life is in danger. There is also no counter-indication for Caesarian sections, which provides another example of Judaism moving with the times.

Unlike in Anglo-Saxon societies, however, there are no baby showers or other celebrations before birth. Traditionally speaking, the name of the child is not even discussed until the end of the pregnancy. There is a simple reason for both restrictions: drawing too much attention to the child might bring bad luck to him or her in the future.

In addition, baby names do not have to be Hebrew; in fact, they are frequently English or have their roots in other modern languages. It is also common for Askhenazis, the majority of American Jews, to name their child after a dead relative in the name of remembrance.

Circumcision

One-third of the world’s adult males are circumcised, and so is the majority of male Jewish community.

Eight days after the birth, boys go through the tradition of brit milah, a part of religious law in Judaism. Of course, the procedure can be undertaken later if the physical condition of the child, often an underdeveloped blood clotting system, prevents it. Circumcision is also the time when a boy receives his name. The process itself has its roots in the Torah, when God made a covenant with Abraham, the first circumcised adult. Since then, male circumcision is a sign of strong ties between the Creator and the Jewish people.

Removing the foreskin is performed by a mohel, a religious person, and not a usual doctor as this would disturb the spiritual aspect of the tradition. Mohels are in most instances men, although in some Reformist Judaist communities women are also permitted to perform the religious ritual. It can take place in any adequate place, either a synagogue or one’s house. Circumcision is then followed by relevant prayers and a meal for invited guests, called seudat mitzvah. All in all, it is said to be one of the most important events in a man’s life.

There are, however, a growing number of anti-circumcision organisations and movements all across the globe. The proponents declare male circumcision as “dangerous and stressful”, as putting children in “unnecessary pain” and even as “traumatic child abuse”. They are supported by a small number of, aforementioned, Reformed Rabbis, who declare that uncircumcised children are no less Jewish than their circumcised counterparts.

Bar and Bat Mitzvah

Bar Mitzvah (for boys) and Bat Mitzvah (for girls) refer to a celebration of a peculiar rite of passage. It has been celebrated for more than 500 years and designates the moment Jewish children become adults from a legal point of view. After this rite of passage, they are obliged to observe the commandments and be responsible for their actions. They can also fully take part in religious ceremonies and receive the Torah as well as a prayer book for their future studies. The boys can now wear tefillin during prayer. This small leather box attached to one’s arm and head (containing the Torah) indicates that the boy devotes himself to God’s service by his will, deed and reason.

Essentially, Bar/Bat Mitzvah is nothing more than readings from the Torah (aliyah) with a special weekly blessing which means the child undergoes the most important Mitzvah – Torah teaching. Nevertheless, Bar/Bat Mitzvah usually is a form of joyful celebration, bringing together the celebrant’s whole family. On such an occasion, Jewish families differ in how much they are willing to spend; some of them pay thousands of dollars for DJ’s and entertainers for the guests. There is also delicious food and wine (seudat mitzvah), as well as present-giving (usually in a form of money or religious items). Bar/Bat Mitzvah is a memorable occasion for every adolescent Jew.

Marriage

The Yiddish language, originating from the Eastern European Jewish diaspora, has a beautiful word for ‘soulmate’: a basheret. Basheret is a destined significant other, also a spouse, sought-after by every religious girl or boy. If one cannot find a besheret by him or herself, they usually approach a matchmaker, called shadchan, who professionally introduces single men and women intending to marry. In more religious communities, the potential partners have to make a choice about their common futures just a couple of days after meeting for the first time, but the entire process can take up to a couple of months.

Having found a significant other, the couple goes through kiddushin and nisuin. Kiddushin is a form of betrothal when a woman accepts some form of obligation (for example money or a contract) and legally becomes a wife. The nisuin is when the woman is shown the home of her spouse-to-be and begins the life of wife. Both are a part of every Jewish wedding, and the latter can take form of showing a private room, instead of a house, somewhere where the wedding ceremony takes place.

Other practices include two blessings over wine and placing a ring on the bride’s finger, as is also the custom in other religions and cultures. Then a marriage contract, ketubah, is presented. Before the nisuin itself, seven blessings are read aloud, completed with wine-drinking.

What is characteristic of these celebrations is the smashing of glass by the groom, which is meant to symbolize the destruction of the Temple during the Siege of Jerusalem. Like in other joyful occasions for Jews, there is a moment reserved for reflection on the distressing past. Afterwards, there is a buzzing ceremony which includes dancing, such as the Mizinke or Krenzl. Here, men and women are entertained separately.

When it comes to illicit marriages, there are restrictions in religious communities regarding same-sex ceremonies, underage matrimony and matches between closely related people. However, some Reform and Liberal movements, largely in the UK, do perform same-sex ceremonies following laws passed in 2013.

Death

Like everything in Jewish life, death is also believed to be a part of God’s plan. What is strictly followed is the respectful treating of the deceased. No drinking or eating in front of the dead is permitted as they cannot do such things any longer. No cremation, embalming, open casket nor autopsy or even coffins are permitted as there is belief that the body should be left untouched and in contact with the earth.

After a stated death, the body is purified and swathed in shroud. Simplicity is the key – no deceased should be treated differently and with greater care despite prior cultural and material status.

Mourning takes place in different stages. First, it is common to tear one’s clothes in expression of the greatest grief if the deceased is one’s close relative. Then, in preparation of the burial, the family is left by themselves to experience the distress in peace. After the ceremony, the mourners eat a special meal consisting of bread and eggs; this is also a time when condolences can be extended. In turn, shiva, a seven days mourning time, inhibits pleasurable practices, such as baths or play, and inhibits changing clothes from the funeral, cutting hair or wearing cosmetics. Similarly, shloshim is the time when no celebrations are held. Avelut, the last stage of mourning, is only obeyed by the parents of the deceased and lasts for twelve months in total. During that time, any celebrations or cultural events are omitted.

As it can be seen, all the celebrations in Jewish life, either positive or melancholic, have their own specific colours and qualities that are often beautifully inimitable. It is therefore advisable for us to try to understand them, to somehow immerse in a complex world of rules, religious restrictions and saint commandments.

Edited by Amelie de Paepe

Artwork by Chira Tudoran