By Tom van der Meij

A couple of months ago, The Guardian asked prominent British writers how they coped with the Corona crisis and the lockdown the United Kingdom found itself in at the time. Celebrated novelist Julian Barnes wrote that he had found pleasure indulging himself in the movies of Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, especially the movie The Seventh Seal, which takes place in a plague epidemic in medieval Sweden. Barnes even called it the ‘greatest of plague movies’, a grotesque but, upon watching the movie, hardly deniable statement. Despite the medieval setting and the late 50s recording, the movie’s profound portrayal of death remains fascinating and it’s lessons on life during a pandemic are painfully accurate. The Seventh Seal can be seen as a benchmark in arthouse movie history.

As mentioned, the movie is set in medieval Sweden, noticeable by the clothing and horses in the first spoken scene, where we meet the main characters. First of all, the knight Antonius Block, played by the late Max von Sydow, arrives at a rocky beach somewhere in Sweden, exhausted from a crusade. On the beach, Block has an encounter with the second important figure in the movie, Death (Bengt Ekerot), and the following interaction takes place:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f4yXBIigZbg

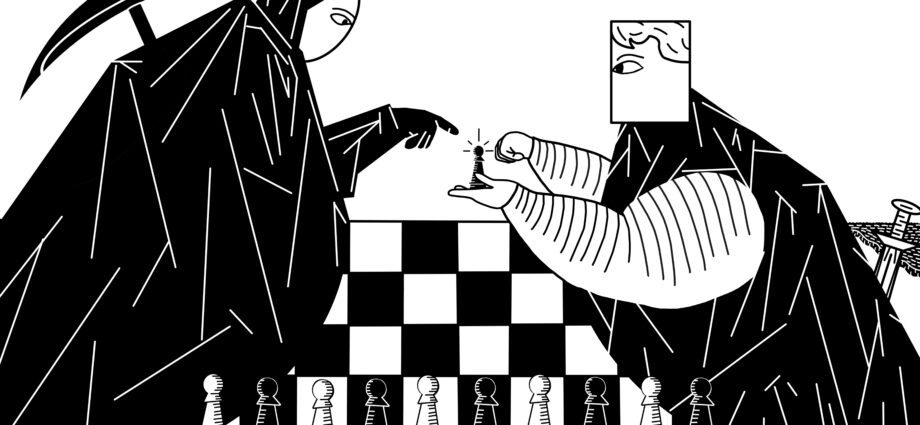

It is an interesting and iconic scene for multiple reasons. Most of all the imagery of Death, which strikes the viewer as both recognizable and very original. Recognizable is the image of the Grim Reaper. The man or spirit that comes to collect the souls of the deceased, often holding a scythe, is as old as the hills and frequently returned in medieval writing and imagery. It fits well in the dark scenery of the middle ages, where religious thinking and sudden deaths created a mystification, and intolerable anguish, of death. But it is most of all Bergman’s version of the Grim Reaper that makes the scene original. He manages to create a personification of the Grim Reaper that is not immensely scary or threatening, but rather natural and mysterious. This can be seen in Block’s reaction, who does not seem caught off guard by the figure’s appearance.

Block’s sturdiness is the backbone of the surprising dialogue that follows between the two characters. How naïve of the knight, perhaps, to think that he could trick death, to think that he would be able to escape the inevitable. But as he confirms, his body might be able to die, but his spirit isn’t yet.This strategy apparently intimidates Death, and provokes him into playing a chess game with Block. The relationship between the Grim Reaper and chess is another medieval allusion, specifically referring to a mural painting in an old church in Sweden.

Because the Grim Reaper turns out to be a figure that weighs his words well, Block does not get any guarantees that winning the game of chess will keep him alive, but for the time being, he has been able to postpone his death. That Bergman decided to put this scene at the very beginning of the movie shows the experience of the filmmaker; the presence of the Grim Reaper sets an intriguing premise that sticks with the viewer. The scene has made a clear disclosure, namely that Block’s time has come, but that it might in the end be up to Block himself to decide what happens next.

After this initial chess conversion, Block, together with his ‘’squire’’ Jöns (the medieval equivalent for personal assistant), proceeds into plague afflicted Sweden and meets a variety of interesting characters: a priest paining the so-called dance of death in his church, a group of traveling performers trying to make a living and distract people’s minds from all the suffering around them, a presumed witch who allegedly cooperated with the devil and deemed to be burned, and a desperate blacksmith who lost his wife to an actor.

The plague affects all these people’s lives and mental wellbeing, just as the current pandemic affects ours. With some creative thinking, it is not that hard to see parallels to our time, although the movie often portrays them in a much more uncivilised manner and concerning a much deadlier disease. In the movie, there is a thief stealing jewelry from deceased plague victims, there is a man who laughingly tells his companions they better enjoy life while it lasts as an antidote to the increasing fear-mongering around them, and there are peasants completely stunned in fear by the mysterious virus. The parallels between the movie and modern day are the strongest in the scenes that purely focus on dialogue. In these scenes we recognize the way in which both medieval and modern day human beings cope with an intangible situation. During a tavern table scene, between three not earlier seen characters, the following dialogue erupts:

It’s true, the plague has swamped the west coast. People die like flies! … They talk of the last day. And all the omens certainly are terrible. … People are crazy. They flee inland and take the plague with them! … If it’s as they say, then we’ll have to enjoy life as long as we’re standing!

At the same time, it is interesting how the narrative in the movie completely differs from the reality we see today: in The Seventh Seal, the plague is seen as a punishment of God. It is believed that the humans have done something wrong or immoral that they need to pay the price for. As it is mankind that has sinned, it is mankind that needs to suffer. Perhaps the most shocking scene of the movie shows groups of Christian believers seeking punishment by whacking each other and themselves with brooms and sticks, only increasing the overall suffering. Today, we mostly apply a rational and academic approach to determine the origin of a virus, which partly ignores the influence of mankind. It might, however, be appropriate and even necessary to look at ourselves as individuals and as societies as well when analyzing our current crisis. Not to point towards a guilty person or to chase each other with brooms or sticks, but merely to look at our current influence in the grander scheme of things. To assess, for example, the way humans treat animals, which created the basis for the mess we’re in at the moment, and whether we should change our lifestyles to prevent more viruses from breaking out.

The antithesis of life and death which surrounds the characters, and the diverging approaches they adopt to the plague features as the leitmotif during the whole movie. Death is, literally and figuratively, all around them, and even more so for Block and Jöns, who have the bloody memories of the crusades fresh on their minds. When Block talks to the witch they meet along the way, he asks her to get him into contact with the devil, a desperate attempt to get answers to his religious doubts he confessed in an earlier scene. In the church where they met the painting priest, Block, initially unknowingly, has a new conversation with Death. He confesses his doubts about God’s existence, the discomfort he feels about the lack of answers he receives from Him, and his anxiousness of death arising from God’s silence. After the crusade, Block feels doubtful about his fate and is confused by his thoughts. It is a scene full of mystification and unanswered philosophical questions:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s1ZAMiW4yEQ

That Bergman decided to make a movie focused on themes such as death and religion can be explained partially by his own youth, as Bergman grew up in a conservative and religious family, where theological discussions and religious imagery dominated. Although he lost faith in Christianity at a considerably young age, he never lost his interest in its influence on the human mind. Various movies he made in the 60s relate to this theme, such as the 1961 family drama Through a Glass Darkly, in which the main character has visions of meeting God. The idea of meeting the inconceivable apparently stuck with Bergman. That Block has lost his faith after the crusades is also an obvious link to the zeitgeist of the 50s: after the devastation of the Second World War and the cruelties of the Korean War, many young people must have had similar thoughts as Block, doubting whether a God exists who allows such horrors to occur, and simultaneously perhaps experiencing an urge for the straightforwardness and austerity of the church. Bergman managed to put these 20th century thoughts in a medieval setting.

What adds to the captivating storyline of the movie and the strong acting of von Sydow and Ekerot, are the technical aspects of the scenes. The frequent use of close-up shots, for example, works very well with Block’s face. We see the determination and doubt in his eyes when he faces Death, and joy when he finally reunites with his wife. Bergman also uses a lot of black-white contrasts in the movie: rocky landscapes against cloudy backgrounds, the roaring fire that ends the life of the which with a dark forest in the distance, and of course the contrast between the black robe of the Grim Reaper and his bright white face. Or, perhaps even more striking, the stark black and white contrast of the chess game that the Grim Reaper is referring to in one of the first scenes. In this way, Bergman lets the contradiction between life and death resonate endlessly in every single part of the movie.

The impact of The Seventh Seal on western moviemaking cannot be overstated: it is hard to identify a better and more convincing personification of Death than Ekerot’s embodiment. The movie was Bergman’s breakthrough as a moviemaker, and his ability to bring joyfulness to such a heavy and complex theme as death, as well as mixing philosophical themes with entertainment, has been admired by fellow movie makers such as Woody Allen and Martin Scorsese. And more than 60 years later, the themes of The Seventh Seal do not feel outdated or irrelevant. Quite the opposite; Bergman’s classic is as relevant as ever.

The movie can be watched for free here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mbgiWPJLSsM

Edited by Juni Moltubak

Artwork by Oscar Laviolette