By Chira Tudoran

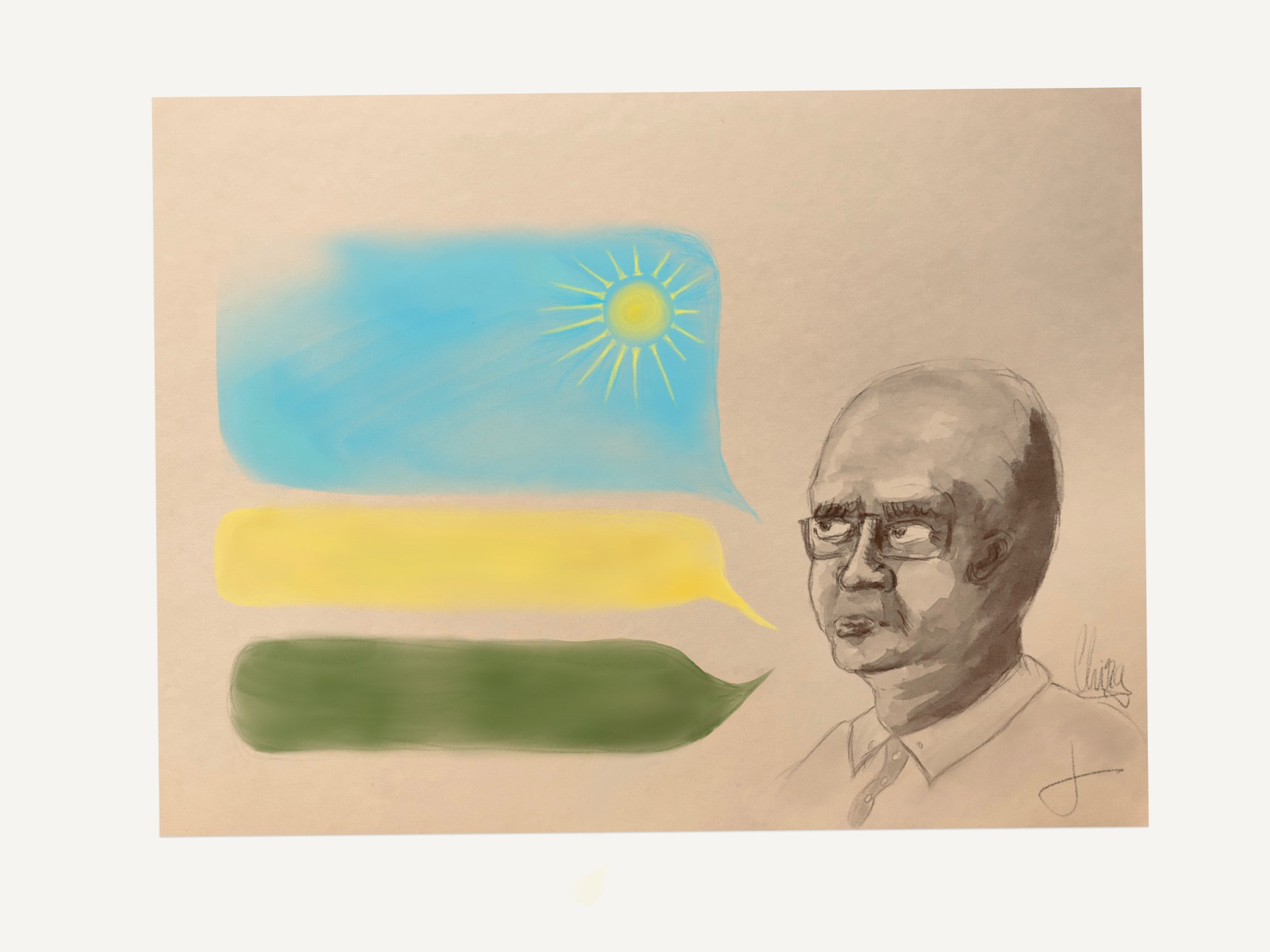

Herbert Ndahiro, first Secretary of the Ambassador of Rwanda in the kingdom of the Netherlands gave the first part of a guest lecture on the historical and political perspectives on the genocide of 1994. This was organized by the Custodia study association. The guest lecture took place at the Wijnhaven campus of Leiden University in the Hague.

Although the history of the Rwandan genocide is controversial, the first Secretary explained how the Rwandan genocide came to be a long time before 1994. He began with the genesis of the problem, the Scramble for Africa. How the lives of Africans were changed, especially in Rwanda under Belgian rule. But why was Rwanda so important to Belgium? It had no minerals and it

was a small country. The answer is that it was strategically important, as it had easy access to the railway system. Access to Mombasa was and still is crucial for the landlocked countries of the African continent.

The Secretary’s first point in the lecture was how colonial authorities racialised the differences between the Hutu, Tutsi, and the Twa. Prior to that, these were social classes, and they were all one people, with a shared culture and shared language. It was under the auspices of European academics that the Rwandan people became ethnically divided.

Mr. Ndahiro classified the 20th century of Rwanda as such:

The “Divide and rule” policy era, which took place between 1926 and 1933. Where the European elites befriended and flattered the Rwandan chiefs. They spoke of similarities between themselves and the Tutsi, such as being tall, having a pointed nose, being slim, etc. This was followed by a classification of the population, exemplified by the use of identity cards. These cards mentioned which “ethnic” background a Rwandan was, along with whether they were naturalized or not. In this context naturalized means growing up with the Western values of the elites. The consequence is that the naturalized Africans would relate more to Europeans rather than fellow Africans. Hence, the naturalized Africans were elevated in status in this new social system.

This was followed by the “Drums of independence” era of the 1950s. A moment in time when the majority of African countries started gaining sovereignty from their former colonial powers. What is interesting was how much power the catholic church still had in Rwanda. The Hutu Manifesto of March 24, 1957 would have not been published without the catholic church’s stamp of approval. This was a political manifesto written by nine Hutu intellectuals to the vice-governor general of Rwanda. It stated how the Hutus needed to be liberated from the Tutsis and Belgians which oppressed them. The Hutu Manifesto set the stage for the tragedies that had yet to come.

Then came the era of the MDR-Parmehutu (French: Mouvement démocratique républicain – Parmehutu), between 1959 and 1961. Also known as the Party of the Hutu Emancipation Movement. They affirmed and implemented the supremacy of the Hutu majority over the Tutsi minority.

Afterwards was the First exodus of Tutsi in November 1959, where many Tutsis had to flee their country due to the new political climate. Many died on their journeys as refugees, especially elderly, women, and infants. Ndahiro told the students in the audience how Bertrand Russell, a British philosopher, declared the 1963 Tutsi massacre the worst after the Holocaust.

In the words of the spokesman, the genocide was a process. Nothing to this extent happens in a day. That is why for the Rwandan genocide, certain steps had to be taken. The eight phases of the genocide were: Classification, Symbolism, Dehumanization, Organisation, Polarisation, Preparation, Extermination, and Denial.

The last one, the denial, is the one that still brings the most grief. With other tragedies, the victims are remembered, yet the Rwandan genocide is renounced and rebuffed.

If there is denial, then there is no story to tell. Without acknowledgement for the past, future generations are cursed with repeating the same mistakes. Once again they will be vulnerable to the rhetoric of pseudoscience and give in to their greed and pride, as the chiefs. That is why learning the history of such an event is pivotal to us, either African or European. We cannot untangle the embroidery of the past but we can weave a brighter future for ourselves.

Thank you to the Embassy of the Republic of Rwanda in the Hague for giving the guest lecture.

Edited by Hidde van Luenen

Artwork by Oscar Laviolette