Why do we keep being shocked by far-right election results?

Written by: Daria Aron

As I started to write this article on the evening of Sunday, 24th of November 2024 I was watching the election results of the first round of the Romanian Presidential Elections. As the exit polls began rolling out I saw a candidate whom I barely knew with extreme fascist, anti-semitic and pro-Putin views getting a worryingly large share of the votes across the nation. To my even bigger surprise, much of his support was originating from the country’s sizeable diaspora – with over 5 million Romanians living abroad. While I expected to see the far-right make gains, as we have seen across Europe, I did not predict its most extreme form to win and potentially lead my country. As these results from every single voting station began trickling in, my parents and I kept scratching our heads (or rather pulling our hair out) in complete disillusionment about how this was even possible. Are we that detached from reality, or from other people in our country?

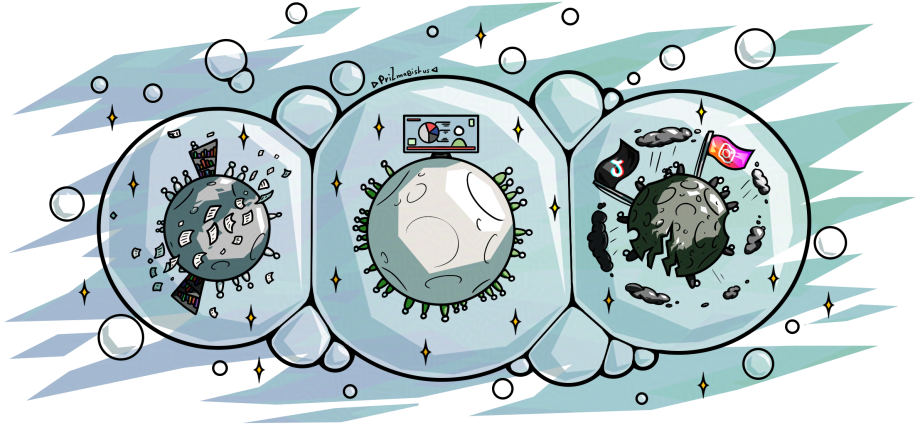

For more context, Independent candidate Calin Georgescu, the more extreme candidate who was completely ignored in the pre-election campaign coverage got the most amount of votes, more than the current Prime Minister who was thought to dominate this round of voting, and more than the leader of the far-right party AUR, George Simion. As for Georgescu, early analysts are pointing to his successful social media strategy, executed mostly on TikTok (with suspicions that most of the funding he received was used for buying bots which furthered his message). This aided in targeting specifically the economically weaker subsets of the population and the diaspora, especially in the moderation of the other extreme right-wing candidate Simion. Even though TikTok had this immense influence, it is not the only reason to blame for this result. We have seen this general shift away from traditional media towards social media for more than a decade, with TikTok being just another platform (albeit one where users more easily influence algorithms than others).

Speaking with friends from other countries in the past months, I quickly noticed I wasn’t the only one wracking my head around this. One friend expressed the following about the US elections: “I was libmaxxed and in a bubble”, which in other words means that he was stuck in a liberal bubble which convinced him Kamala Harris had an incredibly good chance at winning. Similar sentiments were expressed around the European Parliament elections in June which also saw a significant increase in far and extreme-right representation, the German state elections earlier this year as well as the descent of Dutch, Austrian and Italian politics into the same path. With this phenomenon, I tend to see people not only in my circle but trusted analysts and specialists, having covered politics for years if not decades, be as shocked as I am. So, how is this happening? Are we all in completely different ideological bubbles and completely disillusioned?

One of the main and most consequential differences between the groups who have begun voting for right-wing populist parties and everyone else is education. This refers not only to formal education but general education about the country’s processes and relations with other states, and even more importantly, critical thinking. Due to this general lack of knowledge, centrist and liberal politicians’ praises about inclusivity and the EU, and how these have truly influenced the nation fall on deaf ears. For example, suppose most of the media consumed by a person focuses on the topic of EU overreach and how this might eliminate this person’s job, then this hypothetical person will not be open to perceiving any other EU-funded projects positively, wholly ignoring them. This then translates to a complete tunnel vision of politics which creates a veil of ignorance of any benefits received from this more liberal perspective.

Additionally, in the absence of a large migratory movement, such as those in Western Europe, far-right politicians attempt to focus on other threats of a similar nature such as the ever-controlling Brussels and a traditional fallback pastime – anti-semitism. Furthermore, an important trend seen across Europe but especially in Central and Eastern Europe is a move away from the mainstream parties which are a source of disappointment due to the perceived lack of progress since each country’s respective regime change approximately 35 years ago. Due to those frustrations, many individuals, especially those in the younger generations do not feel included in their country’s democratic processes. This is exacerbated by the increase in the use of social media as a news source, one which through similar tactics as those used by Georgescu, can manipulate citizens and even entire elections. In Romania, manipulation on social media platforms has created an overall negative view of democracy which explains the increasingly pro-Russian and authoritarian views among subsets of the population. All of these factors taken together, make it so that this sub-group of the population unconsciously ignores more liberal pro-EU politics due to a fear for their futures, which also translates into the mainstream parties ignoring them in turn.

So how does this translate to delusion? As with typical dynamics, a group always tends to feel superior to another. In this case, this superiority translates into a general disgust towards the way other individuals voted also powered by the fear of how these extreme-right-wing politics might manifest. Due to this ideology difference, we tend to dismiss these sub-groups until they come to vote, and this divide is ever so visible. In turn, we then tend to blame these individuals and use their lack of education as a reason to belittle their opinions and votes continuing the cycle of ignorance. And coming back to our original question – are we deluded or wishful hoping for a better future? Probably both, and I would hope that by making this realisation we are on the right path.

Coming back to Georgescu, besides his strategy, his politics carry on from the same prejudices and insecurities in other European nations. From supporting pro-Christian traditional messages in the face of wokeness to highlighting economic disparities, Georgescu also focused on rhetoric increasingly being used – referring to the anti-semitic and fascist Legionaire movement of the 1930s and 1940s. Done by other politicians, including Simion and MEP Diana Sosoaca, Georgescu continued this rhetoric highlighting the good parts of the regime (even though this led to him receiving fines as referring to the movement and its crimes-against-humanity-committing leaders being against the law). He also referred to the leaders of the movement as national heroes. The success behind this rhetoric does not lie purely in the prejudices of the Romanian people which are further instigated by Georgescu’s statements. Instead, such politicians use the well-known lack of critical thinking of their target group to tie the movement’s success to the supposed patriotism that the movement relied on – a Romanian movement for the betterment of the lives of Romanians, whereby prejudices are seen as the means to achieve this. In turn, the targeted citizens tend to appreciate the passion of these politicians and interpret their approach as one of truth and sincerity, unlike the mainstream parties. It is exactly this which makes these politics so dangerous, people’s insecurities and lower educational levels which are targeted for instigating hate and democratic backsliding.

Elections are not done for Romania this year, with parliamentary elections this past weekend mirroring an increase in the far-right trend, and the second round of the presidential elections this upcoming weekend which will determine the head of state of the Country for the next five years. In this round, Georgescu will face the centre-right liberal Elena Lasconi. If Georgescu were to be elected, this would have several implications for Romania’s relationships with the EU and NATO, as Georgescu is a sceptic of both, as well as with Ukraine, which Georgescu thinks is an invented state. As Romania remained relatively stable while other European nations succumbed to various far-right parties, this result was a blow to all the people who were hoping for a more inclusive, modern and European Romania.

Edited by Joanna Sowińska, Illustration by Prizmagistus